Αναδημοσίευση από jadaliyya

Last September, sixteen-year-old Eman Mustafa was walking with a friend in the village of Arab Al Kablatin Assiut, when a man groped her breasts. She turned to face him and spat in his face. He shot her dead with an automatic rifle as a price for her bravery. Mustafa’s death was an eye-opener call to those who claim that sexual violence is an urban issue. Thanks to human rights organizations and activist groups, Eman’s killer was sentenced to life imprisonment in June 2013.

Violence against women across historical, cultural, and national divides continues to be a socially accepted practice, if not a norm. In the realms of both policy and social awareness, we have collectively failed to tackle this issue with serious rigor. As a result, we seem to be witnessing an increase in sexual violence and brutality.

In Egypt, sexual harassment is widespread and touches the lives of the majority of women whether on the streets, in public transportation, or at the work place, the super market, or political protests. It is true that sexual harassment still lacks a unified definition, but it is not difficult to identify unwelcome verbal or physical sexual violation. Many Egyptians, women included, are unclear as to what constitutes sexual harassment. Others sadly, do not think it is a problem. One thing is clear though, and that is the actions of the various governments of the last thirty years have been limited to statements of regret and unmet promises.

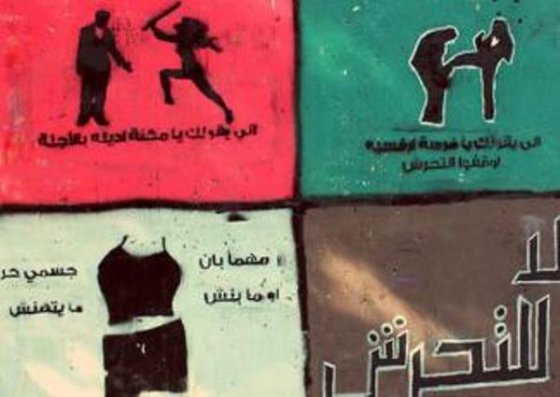

The word taharrush (harassment) is a relatively new term in the daily lexicon. Until recently, sexual harassment was referred to as mu‘aksa (flirtation). That term alone reveals the multiple layers of denial, misogyny, and violence Egyptians must confront in tackling sexual harassment. In addition to rape and physical assault we must equally tackle name-calling, groping, and the barraging of women with sexual invitations. All of these acts normalize violence and hatred against women and they must become socially unacceptable.

Even though, for example, Eman Mustafa was a veiled villager, one key argument in the victim-blaming that is salient in our everyday narratives is the common and vulgar perception that sexual harassment occurs when women dress “provocatively.” In fact, the only thing that Egyptians who face sexual harassment have in common is that over ninety-nine percent of them are females.

Over the last decade, Egyptians have been working intensively on spreading both social and legal awareness on sexual violence and harassment. In 2005, the Egyptian Center for Women’s rights launched its “Safe Streets for Everyone” initiative to combat sexual harassment. In 2008, more than sixteen human rights organizations and independent groups formed the “Task Force Against Sexual Violence.” In 2010, that Task Force released its own bill to amend Penal Code provisions on sexual violence. That year too, the volunteer-based initiative Harassmap established a free software method to receive anonymous SMS reporting that it would process into a mapping system. Harassmap’s mission was to render sexual harassment socially unacceptable.

Over the past two years, activists have formed many other independent movements and online groups that raise awareness, empower women to stand up against gender-based violence and speak out by sharing testimonies and ideas to combat sexual harassment, and in some cases, expose the perpetrators. After Eman Mustafa’s death last September, anti-sexual harassment protests were held at Assiut University to condemn the murder of a girl who fought for her bodily rights.

Women who have suffered from sexual harassment are usually reluctant to tell their stories, fearing reprisals and the dreaded label of the agitators. Nevertheless, if there is any noticeable progress in fighting sexual harassment in Egypt, it would be the rise in the number of women who are speaking up about their experiences and filing reports against their offenders. Another important development has been the formation of independent volunteer-based groups who fight sexual violence on the ground across the nation. In 2010, Harassmap received requests to expand their campaign to Alexandria, Daqahliya, and Minya. This year, Harassmap has expanded to sixteen governorates other than Cairo. With the help of more than 700 volunteers nationwide, Harassmap is reaching out to rural communities to end social acceptability of sexual harassment.

In June 2008, Noha al-Ostaz experienced a form of sexual violence on a Cairo street. She was confident that ignoring the behavior of the offender was ineffective. With the help of a friend and a bystander, Al-Ostaz managed to take the offender to a police station and file charges against him. Three months later, and for the first time in Egypt, the offender was sentenced to three years in prison on charges of sexual assault. Al-Ostaz paved the way for other women to stand up for their rights. Her action has encouraged several to pursue harassment charges against assailants.

Continue reading →