[youtube]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cceAp2I_Kw8[/youtube]

Daily Archives: July 16, 2013

#taharrush Sexual Violence in Egypt: Myths and Realities

Αναδημοσίευση από jadaliyya

Last September, sixteen-year-old Eman Mustafa was walking with a friend in the village of Arab Al Kablatin Assiut, when a man groped her breasts. She turned to face him and spat in his face. He shot her dead with an automatic rifle as a price for her bravery. Mustafa’s death was an eye-opener call to those who claim that sexual violence is an urban issue. Thanks to human rights organizations and activist groups, Eman’s killer was sentenced to life imprisonment in June 2013.

Violence against women across historical, cultural, and national divides continues to be a socially accepted practice, if not a norm. In the realms of both policy and social awareness, we have collectively failed to tackle this issue with serious rigor. As a result, we seem to be witnessing an increase in sexual violence and brutality.

In Egypt, sexual harassment is widespread and touches the lives of the majority of women whether on the streets, in public transportation, or at the work place, the super market, or political protests. It is true that sexual harassment still lacks a unified definition, but it is not difficult to identify unwelcome verbal or physical sexual violation. Many Egyptians, women included, are unclear as to what constitutes sexual harassment. Others sadly, do not think it is a problem. One thing is clear though, and that is the actions of the various governments of the last thirty years have been limited to statements of regret and unmet promises.

The word taharrush (harassment) is a relatively new term in the daily lexicon. Until recently, sexual harassment was referred to as mu‘aksa (flirtation). That term alone reveals the multiple layers of denial, misogyny, and violence Egyptians must confront in tackling sexual harassment. In addition to rape and physical assault we must equally tackle name-calling, groping, and the barraging of women with sexual invitations. All of these acts normalize violence and hatred against women and they must become socially unacceptable.

Even though, for example, Eman Mustafa was a veiled villager, one key argument in the victim-blaming that is salient in our everyday narratives is the common and vulgar perception that sexual harassment occurs when women dress “provocatively.” In fact, the only thing that Egyptians who face sexual harassment have in common is that over ninety-nine percent of them are females.

Over the last decade, Egyptians have been working intensively on spreading both social and legal awareness on sexual violence and harassment. In 2005, the Egyptian Center for Women’s rights launched its “Safe Streets for Everyone” initiative to combat sexual harassment. In 2008, more than sixteen human rights organizations and independent groups formed the “Task Force Against Sexual Violence.” In 2010, that Task Force released its own bill to amend Penal Code provisions on sexual violence. That year too, the volunteer-based initiative Harassmap established a free software method to receive anonymous SMS reporting that it would process into a mapping system. Harassmap’s mission was to render sexual harassment socially unacceptable.

Over the past two years, activists have formed many other independent movements and online groups that raise awareness, empower women to stand up against gender-based violence and speak out by sharing testimonies and ideas to combat sexual harassment, and in some cases, expose the perpetrators. After Eman Mustafa’s death last September, anti-sexual harassment protests were held at Assiut University to condemn the murder of a girl who fought for her bodily rights.

Women who have suffered from sexual harassment are usually reluctant to tell their stories, fearing reprisals and the dreaded label of the agitators. Nevertheless, if there is any noticeable progress in fighting sexual harassment in Egypt, it would be the rise in the number of women who are speaking up about their experiences and filing reports against their offenders. Another important development has been the formation of independent volunteer-based groups who fight sexual violence on the ground across the nation. In 2010, Harassmap received requests to expand their campaign to Alexandria, Daqahliya, and Minya. This year, Harassmap has expanded to sixteen governorates other than Cairo. With the help of more than 700 volunteers nationwide, Harassmap is reaching out to rural communities to end social acceptability of sexual harassment.

In June 2008, Noha al-Ostaz experienced a form of sexual violence on a Cairo street. She was confident that ignoring the behavior of the offender was ineffective. With the help of a friend and a bystander, Al-Ostaz managed to take the offender to a police station and file charges against him. Three months later, and for the first time in Egypt, the offender was sentenced to three years in prison on charges of sexual assault. Al-Ostaz paved the way for other women to stand up for their rights. Her action has encouraged several to pursue harassment charges against assailants.

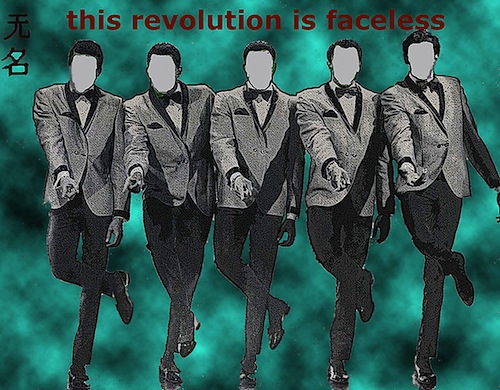

Wu Ming: Είμαστε όλοι ο Φλεβάρης του 1917 ή πώς να μιλήσουμε για την επανάσταση

Αναδημοσίευση από barikat.gr

Πριν μερικές εβδομάδες, ο Guardian δημοσίευσε ένα άρθρο των Αντόνιο Νέγκρι και Μάικλ Χαρτ, με τίτλο «Οι Άραβες είναι οι νέοι πρωτοπόροι της δημοκρατίας». Οι συγγραφείς επιχείρησαν να παρουσιάσουν ένα πλαίσιο ερμηνείας των πρόσφατων λαϊκών ξεσηκωμών σε Βόρεια Αφρική και Μέση Ανατολή. Σε κάποιο σημείο γράφουν:

«το να αποκαλούμε αυτούς τους αγώνες «επαναστάσεις» φαίνεται να παραπλανεί τους σχολιαστές, οι οποίοι υποθέτουν ότι η πορεία των γεγονότων πρέπει να υπακούει σε λογικές 1789 ή 1917 ή εν πάσει περιπτώση σε άλλες περασμένες ευρωπαϊκές επαναστάσεις εναντίον βασιλιάδων και τσάρων».

Το ερώτημα που θέσαμε ενώ ετοιμάζαμε αυτήν την ομιλία ήταν το εξής: Μπορούμε να ταυτίσουμε ένα σύγχρονο ξεσηκωμό με επανάσταση χωρίς να παραπλανηθούμε με τον παραπάνω τρόπο; Και πώς μπορούμε να περιγράψουμε μια σύγχρονη επανάσταση;

Δεν υπάρχει αμφιβολία ότι τα πρόσφατα γεγονότα σε Βόρεια Αφρική και Μέση Ανατολή, και ιδίως οι αγώνες σε Τυνησία και Αίγυπτο, άγγιξαν όλους και όλες μας, άγγιξαν τη φυσική μας υπόσταση σε ολόκληρη την Ευρώπη και το δυτικό κόσμο. Σε μια πρόσφατη διαδήλωση στο Λονδίνο, μερικοί φορούσαν μπλουζάκια με το σλόγκαν «ΠΕΡΠΑΤΑ ΣΑΝ ΑΙΓΥΠΤΙΟΣ-ΔΙΑΔΗΛΩΝΕ ΣΑΝ ΑΙΓΥΠΤΙΟΣ-ΠΑΛΕΥΕ ΣΑΝ ΑΙΓΥΠΤΙΟΣ». Και παρ’όλα αυτά η δημόσια συζήτηση σχετικά με το ζήτημα είναι συχνά ρηχή και δημιουργεί σύγχυση, με όλες τις παγίδες και τα ιδεολογικά όπλα που θα αναλύσει ο σύντροφός μου WM2 στην ομιλία του.

Εγώ θα σταθώ στο ότι, ενώ προσπαθούμε να αποφύγουμε τέτοιες παγίδες, πρέπει ταυτόχρονα να αναζητούμε «υγιώς σχιζοφρενικές» αφηγήσεις για τις επαναστάσεις. Αυτό σημαίνει, αφηγήσεις, οι οποίες αφ’ενός να μεταδίδουν την πολλαπλότητα της διαρκούς επαναστατικής στιγμής και αφ’ετέρου να έχουν τη δυνατότητα να μας απελευθερώνουν από τα αντανακλαστικά εκείνα που προκαλούνται από κάθε είδους προδεδομένες, «παθολογικές» σχέσεις της καθημερινότητάς μας.

Τέτοιες «υγιώς σχιζοφρενικές» αφηγήσεις θα μπορούσαν να αποτελούνται από αναφορές στον 20ό αιώνα και την ευρωπαϊκή επαναστατική παράδοση, χωρίς όμως απρόσμενες ή και προκαλούσες σύγχυση γενικεύσεις* ή υπεραπλουστεύσεις. Νομίζω ότι μια τέτοιου είδους προσέγγιση θα βοηθούσε να καλύψουμε το χάσμα μεταξύ, αφ’ενός, αναλυτών -όπως ο Χαρτ και ο Νέγκρι- οι οποίοι τείνουν να δίνουν υπέρμετρη έμφαση στην ασυνέχεια με τους αγώνες και τις επαναστάσεις του 20ού αιώνα (πχ, ασυνέχειες μεταξύ των σύγχρονων λαϊκών μαζών και των προλεταρίων του 20ού αιώνα ή μεταξύ της σύγχρονης «Αυτοκρατορίας» και του τοτινού ιμπεριαλισμού) και αφ’ετέρου αναλυτών όπως ο Σλάβοι Ζίζεκ και ο Αλέν Μπαντιού. Οι τελευταίοι κάνουν συνεχείς αναφορές στην ιστορία των επαναστάσεων του 20ού αιώνα, δίνουν, ωστόσο, κάποτε την εντύπωση ότι οι αναφορές τους αυτές στόχο έχουν να προκαλέσουν σοκ στο φιλελεύθερο κοινό, παρά να παρέχουν αλήθινή βοήθεια στην παρούσα μάχη που διεξάγεται.

Στην ομιλία μου θα αναφερθώ σε παραδείγματα τέτοιων «υγιώς σχιζοφρενικών» αφηγήσεων της επανάστασης. Τούτο θα το κάνω συγκρίνοντας δύο έργα που παρουσιάζουν τον τρόπο που η ιταλική εργατική τάξη έβλεπε τη Ρωσική Επανάσταση του Φλεβάρη. Τα έργα αυτά είναι αφ’ενός η περιγραφή του Μαρσέλ Προυστ στον δεύτερο τόμο του Αναζητώντας το Χαμένο Χρόνο και αφ’ετέρου το ποίημα του Βλάντιμηρ Μαγιακόφσκι με τίτλο Εκατόν Πενήντα Εκατομμύρια. Θα ήταν μάλλον φαιδρό να αναζητήσω παραδείγματα σε δικά μας λογοτεχνικά έργα.

And where do the workers stand?

Ανάλυση σχετικά με τη σύνθεση των διαφόρων συνδικάτων και τη θέση που παίρνουν σχετικά με τις πολιτικές εξελίξεις, αναδημοσίευση από Mada Masr

EFITU President Kamal Abu Attiya wrote that “workers who were champions of the strike under the previous regime should now become champions of production.”

Syndicates, unions divided over Morsi’s ouster

Since the events of June 30, divisive fault lines have emerged within the country’s trade unions and professional syndicates, with leading members of these associations taking sides with the new ruling elites or former President Mohamed Morsi’s ousted regime.

Unions and syndicates have been brought to the forefront of this ongoing conflict, as their leadership, loyalties and politics all come under question.

On July 2, a call for a general strike against the Morsi regime issued by the Egyptian Federation of Independent Trade Unions (EFITU) failed to materialize. EFITU’s presidency has since expressed support for the new ruling elites, endorsed by the military council.

On the other hand, prior to and since Morsi’s ouster on July 3, a number of syndicates have moved to show their support for the Islamist president.

Before Morsi’s ascent to power, the Muslim Brotherhood had a negligible presence within Egypt’s blue-collar labor unions, but was tremendously influential within the white-collar professional syndicates. The Brotherhood has historically maintained a strong presence in the Doctors, Dentists, Pharmacists, Veterinarians, Lawyers, Engineers and Teachers Syndicates, winning elections in many of these associations and controlling their boards.

Now, having lost control of the executive and legislative branches of the state, the Brotherhood is resorting to its historic base of power, and, perhaps, their last remaining political refuge — the professional syndicates.

According to Amr al-Shoura of the independent Doctors Without Rights group, the Federation of Professional Syndicates — consisting of some 18 associations — “and especially the Doctors and Pharmacists Syndicates have been and still are actively mobilizing their forces against the June 30 movement, and in support of Morsi.”

Shoura pointed to the bloody events of July 8, where more than 50 pro-Morsi protesters were shot dead by military forces and hundreds of others were injured outside the Republican Guard headquarters, where the ousted president was reportedly being detained.

The following day, a press conference was held at the Doctors Syndicate, where members of the Brotherhood-controlled Doctors for Egypt group announced the formation of a fact finding committee to investigate what it called a “massacre.”

According to Brotherhood sources, at least 85 protesters were shot dead in the incident and more than 1,000 were injured — nearly all of whom were Morsi supporters. According to the Republican Guards and Ministry of Health, though, only 52 were killed and over 200 injured in the incident, including both security forces and protesters.

Independent investigations conducted by the Doctors Without Rights group suggest that “the actual number of casualties may be somewhere between the figures issued by both the Brotherhood and the Ministry of Health. The number of fatalities could be subject to increase,” Shoura says.

He adds that both sides of the conflict were involved in deliberate misinformation campaigns.

“Brotherhood members screened photos and videos during their press conference at the syndicate in which they claimed that women and minors were killed in these clashes. This has proven to be misleading and untrue,” asserts Shoura. Images of dead women and children from the Syrian civil war were allegedly used as Brotherhood propaganda claiming that they were killed by Egyptian security forces.

On the other hand, a media blackout appears to have been imposed on many hospitals who received casualties from these clashes.

“While we strongly denounce the violence and bloodshed, we are wary of the politicized news and statistics coming from both the Brotherhood side and the army’s side,” Shoura adds.

The Doctors Syndicate has announced that it would provide LE5,000 to the families of each of those “martyred” by the Republican Guards.

According to Brotherhood member Abdallah al-Keryoni, the Republican Guards clashes necessitated an intervention by the syndicate.

“Two doctors were shot dead by Republican Guards, another nine were injured after having been shot with live ammunition, and several other doctors were arrested during these events,” he alleges.

“The function of the Doctors Syndicate is to support physicians and to stand up for their human rights. The syndicate is supposed to engage itself in political issues pertaining to health care and doctors’ rights nationwide,” Keryoni says.