Αναδημοσιεύουμε εδώ μια ενδιαφέρουσα συζήτηση γύρω από τις εξελίξεις στην Ελλάδα που λαμβάνει χώρα στα πλαίσια του διεθνούς περιοδικού για την κομμουνιστικοποίηση SIC με αφορμή ένα άρθρο που δημοσιεύτηκε στο brooklynrail.

Where has Syriza taken Greece? Which are the forces at play in the restructuring of the Greek economy? And what are the conditions of its radical critique? What follows is a discussion of Cognord’s text “Changing of the Guards”, including TH’s critical remarks on that text, Cognord’s reply to these remarks and Ady Amatia’s comments on the questions raised in this discussion.

Cognord, “Changing of the Guards”

It appeared that the endless saga of the negotiations between the Syriza government and the European lenders had come to an end. After five months of ferocious zigzags, suspense, and fear, a certain deal had been reached. A sense of relief was radiating from the world press, the technocrats, and government bureaucrats. Whether the deal would be a success or not, however, seemed to depend on whom you ask. For those who wanted to ensure that austerity would continue, the deal was certainly to their liking. Curiously, for those who claimed to be on a mission to end austerity, the deal was also favorable. For those who will be immediately affected by the proposed measures, it seemed that not much had changed. The devil is in the details, some say, and many would have preferred those details to get lost amidst the obscure technicalities. Unfortunately for them, however, even Lorca knew that “ […] under the multiplications, the divisions, and the additions […] there is a river of blood.” The relief and satisfaction that the deal brought about could only have been short-lived. In fact, it could only have provided some gratification to the extent that it remained on paper. For as soon as its measures would have been implemented, the party would have been over.

Gentlemen, we don’t need your organization

In the February 2015 issue of the Brooklyn Rail, I described Syriza’s infamous Thessaloniki Program(its veritable pre-election box of promises) as a minimal Keynesian program, with no real chance of reversing the catastrophic consequences of five years of violent devaluation. Back then, to say this was nothing short of blasphemy. An enthusiastic left was roaming around the globe speaking of a radical left, proclaiming an end to austerity, blowing a wind of change. Criticisms of Syriza and its economic program were cast aside as indications of an unrealistic and arrogant ultra-leftist dogmatism.

Today, the very people who supported Syriza in widely read articles and interviews are forced to admit a certain “moderate Keynesianism” in the initial program as well as a real distance between that program and today’s agreement. The happy chorus has stopped singing about the “end of austerity/Troika/etc.,” and has made a hard landing onto the desert of the real.

It seems it took five months to openly admit what was already clear from the February 20th agreement. And while for those who put their trust in Syriza it is somewhat understandable that hope dies last, for those close to the decision-making process of the Greek government, such naiveté is, to say the least, suspicious. For if something has become crystal clear in the last few months, it is that Syriza was not negotiating with European officials; it was actually negotiating the ways through which the continuation of austerity will be accepted by its own members and by those who will be forced to endure its consequences.

Decline and fall of the spectacle of negotiations

From the February 20th agreement in the Eurogroup onwards, it had become clear that Syriza was in no position to implement its Thessaloniki Program. After it became clear that they had no leverage to impose a discussion on debt reduction and an admission of Greece into the Qualitative Easing program of the ECB (European Central Bank), Syriza’s last chance was to rely on a show of good will from the Troika (which was kind enough to accept a ridiculous name change into “Brussels Group”), in exchange for social and political stability in Greece’s troubled territory. A clearly misunderstood version of the “extend and pretend” policy that the Eurozone has been following since the beginning of the crisis was seen by Syriza as a possible win-win for everyone: both the Troika and Syriza would pretend that austerity is minimized, while its essential character would remain unchanged.

However, a combination of the orchestrated irritation caused by Finance Minister Yanis Varoufakis and his inconsistencies, and the more substantial fact that any lenience towards Greece might spiral down towards Eurozone countries with more significant GDPs, meant that this sort of divergence from austerity was out of the question.

The only remaining way to salvage the spectacle of “negotiations” was to engage in a PR campaign which would offer different narratives to different audiences. In this process, what was a series of humiliating compromises in the Eurozone meetings was constantly transformed into a “harsh negotiation” for the Greek audience. Varoufakis became a cause célèbre, whose ability to annoy German Finance Minister Schäuble became a source of national pride in Greece. A mixture of hope beyond proof, disbelief, and the non-existence of political opposition made the task even easier for Syriza’s think-tanks. To top it up, one only needed to throw in a series of incomprehensible figures and decimal points. The self-evident truth of the abandonment of any prospect of minimizing austerity consequences was mystified through a steady production of numbers and statistics which left even experienced “experts” baffled.

Who gives a fuck about an Oxford comma?

In the last few weeks, the “drama” of the negotiations reached its zenith. Back and forth in Brussels, during meetings upon meetings, technical details and strong words were exchanged. It seemed like both sides did their best to uphold a continuously climactic situation, offering cliffhanger after cliffhanger to the addicted spectators. Will a deal be reached? Will we see a Grexit? Is austerity going to continue, or will the “radical left” government of Syriza restore democracy in Europe? How will the markets, these guardians of truth, react?

As soon as one took a closer look at the negotiations, the disagreements and the actual source of this endless conflict, a cloud of boredom descended. Will the fiscal surplus be 0.6%, 0.8%, or 1%? Will Value Added Tax (VAT) be raised by 2% or 3%, and which exact commodities will these increases affect? Will parametric measures equal 2% or 2.5% of GDP? And what about administrative measures? Will there be an ESM-ECB debt swap?

The ease with which both Syriza and the Troika threw around these numbers was nothing but an indication of their contempt for their actual meaning. For what was there to see behind these numbers but imaginative variations which denoted tax increases, direct and indirect wage and pension cuts, and privatizations? How could one possibly miss the accord between the “radical left” and “neoliberal Europe” in their discussions about the need to modernize, to make the economy competitive, to perform a series of structural reforms that, as we were informed by Mr. Varoufakis, are essential for Greece to “stand once again on its own feet”? Can someone really remain confused after the announcement that paying the (hated and formerly to be abolished by Syriza) property tax of ENFIA was “the patriotic duty of Greek citizens”?

The narrative chosen for the internal audience of Greece in order to transform apples into oranges was not only based on the “creative ambiguity” of the Finance Minister. On the side, the PR hacks of Syriza started cultivating the idea that the lenders were treating them so unfairly that not a single unilateral law can be passed by Greek parliament without the approval of the Brussels Group. And thus, in a simple twist, collective bargaining, the increase of the minimum wage, and other measures aimed at tackling the “humanitarian crisis” were put on ice and delegated to a distant future.

To a certain extent, this intransigence of the Troika was, of course, evident. But it was also clear that Syriza selectively used this fact as a useful alibi. For a lot of people failed to understand how, while any measure that was supposed to relieve impoverished proletarians was blocked by the Troika’s intransigence, this never stopped Syriza from making long-term economic deals with Greece’s most important capitalists.

How can Syriza’s members and fervent supporters explain, for example, the recent handing out of lucrative public works like waste management to Bobolas’s company Ellaktor? Or maybe offer some reasonable justification why Bobolas’s contract to financially exploit the highway tolls was extended to forty-five years? Are we really meant to swallow the idea that the reason behind the new agreement between the Attica local municipality and Siemens (a company under investigation by Syriza’s government for money laundering and corruption) was simply that the deal was “already at an advanced level” and could not be stopped? Last but not least, we would be really interested to hear someone explain (in radical-left fashion, please) the statement by deputy Finance Minister Nantia Valavani that any increase in the taxation of wealthy ship-owners runs against the Greek Constitution.

What was initially only felt as a glitch in the screen of the “first-ever-left-government” soon became a inevitable conclusion. Syriza’s government had decided that its allegiance rested not with those who believed that austerity would stop, but with those (inside Greece and in Europe) who were afraid that a left-wing government might prove unable to implement the “necessary” restructuring that austerity is meant to deliver.

A brief look at the language chosen by Greek officials in the course of the “negotiation” reveals as much. Moving away from the abolition of the Troika, the reduction of debt, the series of immediate measures to deal with the “humanitarian crisis,” the Newspeak of Varoufakis was indicative of their self-understanding and selling point:

A common fallacy pervades coverage by the world’s media of the negotiations between the Greek government and its creditors. The fallacy, exemplified in a recent commentary by Philip Stephens of the Financial Times, is that “Athens is unable or unwilling—or both—to implement an economic reform program.” Once this fallacy is presented as fact, it is only natural that coverage highlights how our government is, in Stephens’s words, “squandering the trust and goodwill of its Eurozone partners.

But the reality of the talks is very different. Our government is keen to implement an agenda that includes all of the economic reforms emphasized by European economic think tanks. Moreover, we are uniquely able to maintain the Greek public’s support for a sound economic program.

Consider what that means: an independent tax agency; reasonable primary fiscal surpluses forever; a sensible and ambitious privatization program, combined with a development agency that harnesses public assets to create investment flows; genuine pension reform that ensures the social-security system’s long-term sustainability; liberalization of markets for goods and services, etc.

So, if our government is willing to embrace the reforms that our partners expect, why have the negotiations not produced an agreement?

Inside Greece, however, the narrative was strangely different. Syriza was proclaiming that it would never cross its “red lines” and would not agree to a program that ignores its mandate, while it started circulating the notion that the aim of the Troika was to bring down the government. This spectacle of a government strongly committed to fulfilling its pre-electoral promises (repeated extensively by the foreign press) was in stark contradiction with the fact that that government had entirely abandoned them, but it did serve a purpose: Syriza’s support increased, while it skilfully pre-empted any ridicule of the “negotiation” process. Interestingly, the Brussels Group and interested parties played along with this narrative. Article after article and statement after statement highlighted the unwillingness of the Syriza government to fulfill its obligations to the lenders, its fragile commitment to the “necessary” reforms, its denial of restructuring. When these explanations appeared to lose their effectiveness, the go-to-villain was ready at hand: Syriza’s internal opposition.

There is really no other way to explain the latest stage of “negotiations” than as a veritable piece of theatre, meant to convince both sides (and the public glued to the screens) that there is such a thing as a “negotiation”—even though its exact characteristics are somewhat slippery. The roles were interchangeable: sometimes it was Syriza who raised the flag of no-compromise; in another case, the “negotiations” were torpedoed by the IMF, which curiously echoed Syriza’s (long-abandoned) demand for a debt restructuring as a prerequisite for any deal. And when in May Syriza came up with a forty-seven page proposal officially declaring their will to continue with austerity, the negotiations collapsed after Eurogroup counter-proposals demanded further cuts at a level not ever demanded in the last five years of non-negotiated austerity. Notions like irrationality and absurdity were hard to keep contained.

Post mortem ante facto

For the past weeks, spectators found themselves trapped in a “groundhog day” experiment: every Eurogroup meeting was announced as “the meeting to end all meetings,” every inability to reach a conclusion was seen as a straight path to Grexit, every time the “markets” reacted negatively to the continued instability … and every single time, the conclusion was a pre-recorded message which proclaimed that “progress has been made, but a lot of work is still needed.”

In this race to the finish, and despite the nonsensical comments, it became clear that what was at stake was merely the ability of Syriza to pass further austerity measures as either a victory or an inevitability. Or both. When it started to surface that Syriza’s own proposal would not be easily accepted by all its members (and, perhaps more importantly, by those who would pay for it), stronger means were employed. The ECB joined the dance, threatening a cut of ELA funds, a move that would force the Greek government to impose capital controls (and essentially pave the way for Grexit), while a variety of European officials started proclaiming that a possible Grexit would not have the devastating results that people think.

Whether this was a conscious decision or not is slightly beyond the point. But the result of this spectacle of absurd intransigence on behalf of the Troika produced a very specific outcome: Syriza found itself in a position to present the basis of its forty-seven-page proposal as the “only realistic ground for any negotiation,” while violently rejecting the (absurd) counter-proposals. This portrayal of Syriza as actually defending “red lines” (both internally and externally), while accepting further austerity, seems to have broken the spell. For the first time, all interested parties seem to agree that a deal has been reached and can be signed by all.

At the moment (this was written on June 28th), all eyes are now on the question whether Syriza will manage to pass this proposal in parliament. Some of Syriza’s own ministers and MPs, have publicly declared that the latest deal is in fact worse than the one the previous government rejected, and proclaim that they will refrain from voting it in. It is debatable whether Syriza will actually manage to convince its “rebels” that the deal is a victory and an inevitable outcome of the “negotiations,” let alone make them adopt an approach that says that this deal “buys Syriza time to focus on the defeat of neoliberal policies.” But here is the catch: this does not change much.

If Tsipras believes that the agreement will not pass in parliament, it is very likely that he will call for elections. At the moment, reasonable polls put Syriza well ahead of any other party, and obviously in a position to gain an overwhelming majority. As a result, elections at the moment would only help Syriza consolidate its position and, more importantly, form a government with the explicit and democratically verified mandate to[…] sign the previous agreement. And this time without any internal opposition.

The only problem with this whole saga lies elsewhere. The agreement signed (either now or after a new election) will impose crippling taxation; it will reduce pensions; it will proceed with privatizations; in short, it will aggravate the very reasons why Greece has been in turmoil (in one way or another) for the last five years. Looking beyond the insignificance of political games and spectacular “negotiations,” the agreement that Syriza wishes to implement might make its European counterparts happy, but does nothing to stop or even minimise the actual crisis and its social consequences. What the last five months have shown is only that the “extend and pretend” policy works well inside the Eurozone. But its troubled times are far, very far from being over.

Update (July 2 [2015])

Just when a deal seemed finally to have been reached between Syriza’s government and the Troika, all hell broke loose. Negotiations broke down, Greece defiantly rejected the Troika’s latest proposal and on June 27th Tsipras announced that a referendum is to be held on July 5th, which many have (mis)interpreted as a referendum on whether Greece will remain in the Eurozone or not. To top it all, banks were closed (until the referendum) and capital controls were put in place forbidding money transfers abroad and limiting daily withdrawals to €60 per day.

As I explained in the article, a deal of this sort would have been very difficult to pass. And this is exactly what Merkel herself hinted to on June 25th, just before everyone was about to sign, when she proclaimed that the real problem is whether it will be signed off on by the Greek parliament (i.e. whether Tsipras can guarantee the compliance of his own party). At the moment, it became quite clear that this was not very likely.

In what can only be explained as the troika giving a (risky yet) helping hand to Tsipras, the signing of this deal was sabotaged by the last-minute addition of a number of inexplicable measures that Syriza had already rejected (while incorporating a series of harsh austerity measures in its own forty-seven-point proposal). Suddenly, Syriza landed back in the seat of a defiant, left-wing government and the Troika appeared once again as an intransigent, neoliberal evil lender.

On the morning of June 27th people woke up to meet a Syriza reminiscent of its pre-election bravado: defiant, drawing red lines that will-not-be-crossed, denouncing European anti-democratic procedures. Only difference, for those who cared to notice, was that this time round, Syriza’s “red lines” included an explicit continuation of austerity with pension cuts, new taxes, and privatizations. Varoufakis had used Syriza’s continued public support as an important selling point. But it looked like this was not entirely ensured.

The announcement of the referendum seems to have the purpose of ensuring this “public support.” And though everyone appeared to be taken by surprise by this development, a closer look at what is at stake reveals quite a lot. The question of the referendum is whether Greek citizens approve of or reject the proposal of the Institutions (Troika) made on June 25th. Not Syriza’s counter-proposal, not a previous Troika proposal (there have been many), nothing of the last five months. Now this means very specific things.

A “yes” vote is quite clear-cut. It essentially means that the majority of the Greek population is willing to allow the Troika to continue shaping its economic policies, with the government reduced to its previous role of simply and hastily ratifying the already-made decisions. A “no” vote, on the other hand (which is what Syriza is propagating), is not as clear. It includes those who wish a Grexit; those who want to continue negotiations; those who would accept an “honorable compromise” with slightly less austerity, and a whole number of others that fall somewhere in between these categories.

Now if a “yes” answer prevails, Syriza will resign (they have already announced that much), since while they will respect the democratic decision of the referendum, they are unwilling to be the ones to implement its consequences. Thus, and most probably, a temporary coalition government will be formed (most likely with the participation of New Democracy, PASOK, and Potami) who will then be charged with implementing the harsh austerity that the Troika’s latest deal included. In the meantime, Syriza can enjoy a position of a very sizeable official opposition, eat popcorn, and wait for the temporary government to announce elections a few months down the road (with Syriza’s victory a most probable outcome). If a “no” answer prevails, Syriza is more or less given a free hand to interpret the result as it sees fit. It can push for a Grexit and a return to the drachma (though they have explicitly said this is not what they want), it can restart negotiations (either from their own forty-seven-point program or from scratch), it can make use of “creative ambiguity” to reach some other deal.

In short, the situation seems to be a win-win scenario for Syriza, something that has not escaped the attention of the main opposition parties which, after trying (and failing) to get the referendum cancelled, are now engaged in a vicious (and mostly hyperbolic) propaganda war which results in stark polarization of Greek society and the adding of votes to the “no” side.

One might chose to believe that European counterparts were genuinely surprised by these developments or not. In any case, their reaction has so far been rather conciliatory: the non-payment of the IMF was officially not treated as a sovereign default, capital controls were not interpreted as a direct path to Grexit, and they seem awfully pre-occupied to ensure everyone that they will do their best for Greece to remain in the Eurozone. The only exception seems to be Germany, whose go-to narrative in relation to the Greek crisis seems to have backfired on them. The constant propaganda that lazy Greeks are being fed German hard-earned money, without committing to any of the reforms and their obligations, has led many in Germany to wish for Greece to be kicked out of the Eurozone. Useful as this fairy-tale might have been in the past, it now appears to have the opposite effect. And Merkel might soon have to come clean and explain that, in fact, Germany will lose its money and start paying for this crisis only if Greece exits the Eurozone.

Cognord

July 13 2015

TH, Remarks on “Changing of the Guards”

1. The insufficiency of the notion of a purely spectacular negotiation.

If we are to follow the machiavelian understanding of a staged negotiation, we are unable to understand what our comrade describes:

And when in May Syriza came up with a forty-seven page proposal officially declaring their will to continue with austerity, the negotiations collapsed after Eurogroup counter-proposals demanded further cuts at a level not ever demanded in the last five years of non-negotiated austerity.

If the continuation of austerity in Greece was the aim, then why was this proposal rejected? Syriza had already capitulated, and this was just a proposal, the 47-pages document could have become a 55-pages one without problem. European capital, and German capital in particular, would have never been able to even dream of such a chance to apply austerity in a ravaged country with a maximum of popular tolerance.

2. The specificity of the current Greek situation.

Understanding Syriza as just another Left to do the dirty job as usual is underestimating both the global crisis and the destruction of the Greek economy and society. Of course, a Jedi has to do what a Jedi has to do, and we are in a position to know a thing or two about any would-be manager of a piece of world capitalism with some traces of a human face. But radical critique has to understand what is new, different, specific, and how all this fits in the local and global inter-class and intra-class configuration. It cannot risk to be understood as leftist denunciation as usual.

3. What motivates the different capitalist forces in their attitude towards Greece?

In such times, globalization does not warrant that every disagreement and every confrontation is fake. There’s some real history going on, not everything is a staging. Radical critique cannot accept to rest on conspiracy theories, although some “conspiracies” do exist. History is not the deployment of a given script.

a.

The explanation by a German greed to reap as much as possible and as quickly as possible from a battered Greek economy is rather out of the question. Everybody, including the IMF and any even remotely respectable economist, knew from the very start that the Greek debt was unsustainable and was never going to be repaid in full. As for real assets, German or other capitalists could easily get what they wanted if they put a somehow decent price.

b.

The explanation by the need to impose German discipline on the rest of the Eurozone is much more plausible, but one should also see what it means. The lesson was already harsh, and the spreads on Italian, Spanish, etc., bonds were bound to rise in case of a Grexit. Did Germany intend to be more generous in such a case? Sheer sizes make this very relative. There can be no doubt that Germany intended to firmly impose its domination in Europe. However, there is also strong evidence that it has also methodically pushed for a Grexit. These last days it was revealed that Schäuble had already proposed a consensual Grexit to the then Greek Minister of Finance Venizelos back in 2011, and even after the ‘agreekment’ he is continuing to do so. A final agreement is not that certain.

c.

A possible explanation could be that Syriza had to be utterly crushed, so that any thought of deviating from the one and only German TINA (or German-European, but let’s say German to make things easier) would be banished for ever. This is true, but the scenario of a ‘very brief passage in time’ for an anti-austerity Left had already been thwarted, as Syriza retained an immense popularity, much stronger than their election score. Why not sit back and watch Syriza dwindle through the application of the very austerity it had been elected to fight? An answer to this question has pointed to the imminent Spanish elections, but the acceptance of austerity by Syriza would have been a sufficient sign to any Spanish anti-austerity manager of capitalism.

d.

The German push for a Grexit contained of course an element of propaganda. The bailout of, especially, German and French banks exposed to Greek debt through the public debt of Greece in 2010, presented the advantage of being able to blame everything on lazy Greeks, not on financial speculation. The same could be conveniently said about rising spreads in Southern Europe or about the recapitalization of Northern European (especially German and Swiss) banks through the draining of Southern European deposits. It is however to be noted that propaganda is never the decisive element. What Germany was pushing for was a compact Eurozone under its sway (I am told that recently there has been much talk in Germany about such a ‘compact’ Eurozone). Which means, among others, a stronger euro than in the case of a loose Eurozone. Some years ago German employers were pushing cries of alarm when the euro was rising compared to the dollar. This year their association declared themselves in favour of a Grexit. The core question is no more a weak euro to boost German exports. A strong and stable euro seems to be more desirable. This makes it cheaper to buy real assets in ailing countries (now Greece, tomorrow Italy, Spain, and so on). But it also means a strengthening of the position of the euro as an international reserve currency. Who controls this, can attract financial placements from all over the world, pay minimal to negative rates of interest on their bonds and, if need be, create money at will to dominate the world and impose a large part of global capital’s devalorization on others. Not bad, except that there is an incumbent.

e.

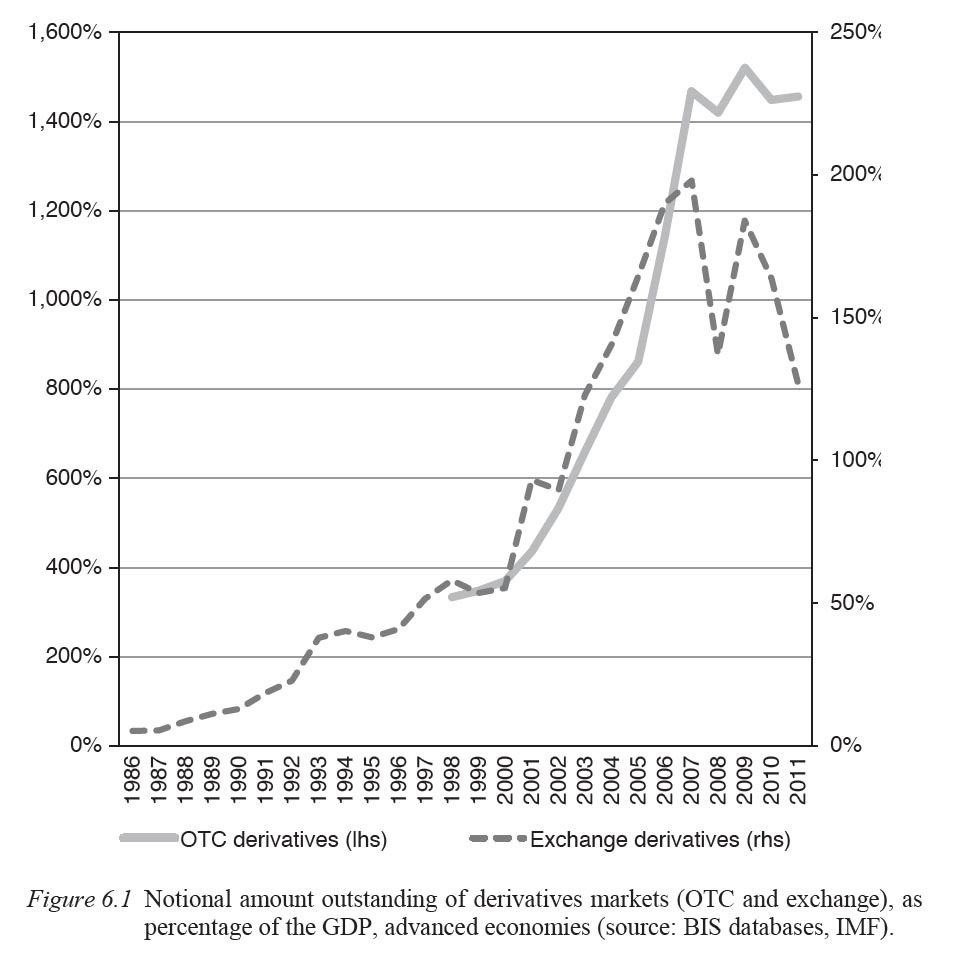

How can one possibly explain repeated, and continuing, interventions by the US administration in favour of some German leniency for a Greece run by Syriza’s government? This came as a surprise to everybody in Greece, and the Greek Vice-Premier Dragasakis admitted yesterday that there would probably have been no agreement without US pressure. This also seems to fit well with an ever bolder attitude by France and Italy during the crucial last week of negotiations (not to mention the spectacular U-turn by Sarkozy in just one week – from Grexit, yes, absolutely, to Grexit, no way). An explanation for the American attitude, popularized by the media, is geopolitics. True, but the US could have insisted on Greece’s continuing membership in the EU and NATO and not bother much about the Eurozone. Another explanation, is American nervousness about the bursting of the [global] financial bubble. Also true, but not enough in itself. On the one hand, the Greek problem was known to everybody and discounted in the markets by the day. This is not usually the way bubbles burst. On the other hand, the financial size of the Greek problem was quite big, but not much compared to a similar situation in, say, Italy, not to mention the colossal size of the world market for derivatives. I think that one has to take account of what I mentioned about international reserve currencies. It is improbable that the US would refrain from fighting the emergence of a compact Europe under German control.

4. How are class relations reconfigured at the level of politics and ideology?

What is the mass behind Syriza in Greece, at least up to the agreement? Sociological insight will not do, whereas [Zaschia Bouzarri]’s remarks about the concrete forms of the decomposition of workers’ identity are more than relevant. Greece is of course not representative of the situation in other countries, but, being an extreme case of a ravaged ex-advanced country, it is useful in showing the shape of things to come. Partisan discourse has been eroded to an unprecedented extent. You can talk to almost anybody, including traditional right-wing voters, about almost anything. You can hardly tell a public servant from a (waged, semi-waged, unwaged, would-be waged or unemployed) worker or a pensioner or a shopkeeper, all united by a sense of a common situation, a common precarity, a common ruin. Voices are low, faces are serious, there is much discussion, confusion, schizophrenia, despair, and much, much anger. The surprising result of the referendum had little to do with hope or conviction; it was essentially anger against fear, and anger largely dominated. “The bastards are ruining our lives, we are not going to say thank you”.

I am seriously tempted to term this a meta-people. Little to do with what we used to call ‘people’, petty existences going after a petty survival, little to do with citizenism, with the affirmation of rights; it’s all about survival, about a community of distress, about an anger against the corrupted, the plunderers of public wealth, the tax-evading plutocrats, and what else. It is impossible to foresee anything, not least because of the actual globalization into the mega-capitalist crushing-pot. However, I cannot stop thinking of this meta-people as a possible foreshadowing of the proletariat to come: not in itself, not for itself, but against ‘them’.

TH

July 16 2015

A Preliminary Response to TH’s Remarks

The article “Changing of the Guards” was written for Brooklyn Rail, after the request of Paul Mattick, and was the third part of a series on articles on Syriza. It does not stand on its own, but is a continuation – and thus quite often an expansion or addition – of points made in previous articles. So, some of the incompleteness that TH. identifies is addressed in previous articles. But, more importantly and beyond that, these are newspaper articles and not theoretical texts. I never claimed that any of them are complete, or that they aim at providing a consistent analysis of the current state of the capitalist crisis – in Greece or elsewhere. In the best of cases, my aim was to provide an expose of what is contradictory, non-sensical, illusory and false in Syriza’s proclamations and policies, in a more or less journalistic way.

Having said that.

The overall argument (in all these articles) is not that the “confrontation” between Syriza’s government and the Troika is “fake”. Rather, I asserted that the “conflict” between Syriza and the Troika was and remains at a spectacular level, which mystifies and politicises their differences in such a way as to present them as substantial. I stand by the assertion that opposing versions of capitalist restructuring are not essentially contradictory, or at least, they represent a contradiction at a level which is spectacular. From the point of view of proletarian subversion, the content of the disagreements, conflicts and breaking points of the “negotiations” is insignificant. As I wrote,

The ease with which both Syriza and the troika threw around these numbers was nothing but an indication of their contempt for their actual meaning. For what was there to see behind these numbers but imaginative variations which denoted tax increases, direct and indirect wage and pension cuts, and privatizations?

For me, this was the content of the “negotiations”. The percentage of VAT, the exact fiscal surplus, the specific amount to be gained from privatisations. In other words, austerity as the common ground, its extent and scope being the point of divergence. Did Syriza and the Troika disagree at this level? It seems so. Does it matter? Only if someone decides to prioritise certain forms of austerity over others.

For this reason, my claim was that the only real content of the “negotiations” between Syriza and the Troika (since February 20th), and since the option of Grexit was rejected by Syriza, was the way in which further austerity would be accepted in Greece without causing a social explosion. This became the essential selling point of Syriza, mirrored in Varoufakis’ quoted passage that Syriza is “uniquely able to maintain the public’s support for a sound economic program”. It does not take much to understand what a “sound economic program” was for Syriza.

The forms through which I expressed this, and the language used, could possibly be misunderstood as the expose of a “given script”, and as such, a “conspiracy theory”. This might well be the case (my English writing skills are limited), but sometimes this interpretation is simply a matter of perspective. Claiming that Syriza is in chorus with an aim of capitalist restructuring could be interpreted as implying a “conspiracy”. Or, it could be seen as a way of rejecting the notion that different understandings of capitalist restructuring are in fact actual contradictions.

TH. claims that “radical critique has to understand what is new, different, specific, and how all this fits in the local and global inter-class and intra-class configuration. It cannot risk to be understood as leftist denunciation as usual.” From the very first text on the Brooklyn Rail, I attempted to stir clear of the typical leftist denunciations of Syriza and tried instead to take Syriza’s proclamations at face value and then explain their inconsistencies. Maybe this was not successful, but this was the aim. In contrast to other radical left texts that I read (which more or less rejected Syriza merely for being part of the State, for being social-democratic etc), I avoided ideological denunciations. I accept that I did not write texts which explained “what is new, different, specific and how all this fits in the local and global inter-class and intra-class configuration”; I admit that this certainly sounds like a worthy undertaking, but – as was once said – “I don’t feel I am up to the task”. Nor do I see my role in this moment to do such a thing. But I don’t think that any analysis which does not live up to these standards is reduced to leftist denunciation.

In reference to the concrete example that TH. mentions in relation to Nantia Valavani’s statement it is, I think, again misunderstood. The question (“I would be interested to hear someone explain …”) is clearly addressed to supporters of Syriza, who kept proclaiming that – at least – Syriza is interested in a certain amount of “social justice”. Taxing the ship owners in Greece was part of Syriza’s pre-election campaign. The abandonment of this “promise” with the excuse that it runs against the Constitution is mere nonsense. But what is the key point here? Do I care if ship owners are taxed or not? Not in the slightest. Do I find this abandonment of a pre-election promise scandalous? That is also nonsense. If anything it is a simple indication that Syriza’s strategy was to promise everything to everyone, a strategy that was abandoned as soon as they became government and got busy establishing and normalising relations with representatives of capitalist accumulation in Greece. There was no hint in my article that Valavani is “on the payroll of ship owners”. That, I grant you, would be a “leftist denunciation”. And though I would not deny such a possibility, I would deny any interest in it. I also fail to see in what way my article gives the impression that the Greek mess is a “nice little crisis as usual”.

TH. points at a supposed contradiction between claiming that the “negotiations” between Syriza and Troika were “staged” (see second paragraph of my response for that) and the fact that Syriza’s 47 page proposal was rejected. But what he is ignoring in this case is what I provide as the undercurrent of these negotiations: the difficulty of making austerity acceptable in Greek Parliament (and by extension, to the Greek public). When the 47 page proposal was made, and it looked that a deal could be reached on its basis, Merkel’s response to the widespread enthusiasm on all sides was indicative: “First, this deal has to be passed by Greek Parliament”. This was the problem of the 47 page proposal. To maintain a spectacle of “harsh negotiations” (which was Syriza’s only selling point internally), the intransigence of the Troika had to be constantly re-asserted. And it was.

This was in effect the aim of the referendum too. It has become pretty obvious that Tsipras was actually expecting (and hoping) that the “Yes” vote would win in the referendum, as this would clear them from being responsible for imposing austerity. The stage was set: the mass media in Greece were clear in their proclamations that a “No” vote would mean that Satan would take charge, and there was not a single European official who did not add that a “No” vote would directly mean Grexit. But the result surprised everyone (Tsipras and the Troika) and their actions after were clearly to pretend like it never happened. This – and the signing of the eventual deal – has brought Syriza into a very fragile position, but given that neither Syriza nor Europeans see any credible opposition at the moment, this fragile position (with a possible coalition in the horizon if Syriza’s “rebels” gain momentum) is translated as a stable scenario. And this could well be the case.

The overall question on what exactly is the aim behind the treatment of the Greek economy by Eurozone officials is probably the key question, but at the same time the most difficult to answer. The most possible scenario that I can come up with is that a process of harsh devaluation will reduce labour costs to such a degree that the Greek economy might become competitive vis a vis other Balkan economies and not other Euro countries. This does not explain everything that has happened, but I have to admit that I find other explanations (such as “Germany’s need to discipline” or the notion of an attempt to “humiliate Syriza”) as vague and very problematic. To say the least, they “psychologise” the actions of centres of capital accumulation.

I agree that Germany’s quasi-open call for Grexit is partly propaganda and partly realistic. But I would explain this divergence between the two as an expression of the internal contradictions of Germany’s self-understanding. I have failed to find any credible account on how a Grexit (and its consequences) can be contained, and in this respect, I find the statement of the head of the Bundesbank (that a Grexit will have tremendous economic consequences for the German economy) more credible than the war cries of Schauble.

My concluding remark in the article is pointing at the same process. The underlying argument is that parts of the German political and economic class have fallen for the propaganda that they have created in relation to Greeks (“German taxpayers have been paying too much for those lazy Greeks”), to the extent that they end up believing it. The reality however (and I am convinced that key players are well aware of that) is that German taxpayers have not paid a single cent so far and they would only be forced to pay something in the event of a Grexit. The logic is quite simple: Germany’s gives loans (not gifts) to Greece that are repaid with considerable interest rates. Furthermore, the continuing crisis and instability means that German (and other) bond yields and borrowing costs are extremely low, something that allows them to save billions of euros (“One study, by German insurance giant Allianz, has calculated that Berlin saved 10.2 billion euros in 2010-2012 because of lower borrowing costs, as yields on its 10-year bonds fell from 3.39 percent to 1.18 percent now.”). On the other hand, it is also pretty clear that a Grexit would mean an immediate non-payment of Greece’s obligations, something that would mean the immediate loss of billions of euros, an amount far beyond the ridiculous 14.4 billion euros that Germany has already put aside in provisions linked to the euro zone debt crisis.

In relation to the US involvement, I fail to see where TH. bases his claim that the US has been lenient towards the Greek government. First of all, signing the deal yesterday (with the help of the Americans, as Dragasakis said) indicates no leniency whatsoever, as the deal signed is far worse than anything signed so far in Greece. Secondly, the position of the IMF (as a key representative of US interests in the eurozone) might appear as rather puzzling, but only at first sight. IMF involvement in the Troika has a clear deadline (March 2016). The continuation of its involvement might well be in the IMF’s interests, but in order to ensure that, they need to impose some debt haircut, not because they align themselves with Syriza, but simply because IMF rules forbid intervention and bailout agreements in countries that have unsustainable debts. The recent DSA of the IMF makes it clear that Greek debt is uviable and that if it is not cut, it will remain unsustainable and would thus preclude IMF continued participation in the program. And it is only through continued participation that the IMF (or else, the US) can ensure their involvement in Eurozone politics.

Last point concerning the mass that supports Syriza. While I would not deny the “decomposition of the workers’ identity”, I would refrain from reaching concrete conclusions of its implications at the moment, let alone come up with a narrative that sees a unification “by a sense of a common situation, a common precarity, a common ruin”. At the moment, the only thing we can say with some certainty is that a very large percentage of the Greek population (I would claim around 60%, in accordance to the referendum results) has simply had enough of austerity and can no longer tolerate it. This does not tell us what they would like instead, but it does point –negatively – at what they cannot live with anymore. For me, the overall situation in Greece indicates that what we should expect in the immediate future is an attempt by political parties (new or old) to take advantage of this huge, un-represented, gap. But it is clear that this (attempt at) representation will take the form of an open support for Grexit and a return to the drachma. The illusion that people’s lives can improve in any way within the eurozone has received its final blows with Syriza’s agreement. So the next “cycle of struggles” in Greece will most definitely take the form of a struggle between those will try to represent the “drachma party” and the rest. What proletarians will do in this context, however, remains to be seen.

Cognord

July 16 2015

Some Thoughts on Cognord’s Text and TH’s Response

[…] How can a ‘people’ avoid being national and citizenist? I have not been in Greece in recent years to be able to clearly know what you mean. When I go back I notice a lot of destitution, physical and mental poor health and of course anger, which is, however, very often mis-directed (racism, frantic attempts to recover from ‘national humiliation’)… What has changed in ‘people’s’ discourse since the squares? That’s a very interesting question and I would like to know more.

Some more thoughts:

Having read Cognord’s texts, as well as his response to TH, I think his reassertion of his approach (to expose Syriza’s inconsistencies or manipulations) clarifies what I have a problem with. While his texts point out inconsistencies that should alarm any ‘believer’, I feel like this approach reduces things to the level of personalities and decision-making. Tsipras said this, Varoufakis said X and did Y, they gave in and they did not live up to their programme, and then they wanted to implement reforms anyway. But why did they do that? Would everything have been different if Syriza were real defenders of the interests of workers? There are certain limits once a self-proclaimed radical finds oneself as head of state, and these are the limits of capitalist reproduction. This is not because people’s personalities become corrupt by power, but because the state plays this very specific role. Example: the state has to manage the pension system, when there are no funds because they were spent on haircuts and debts, and because unemployment is 30%, so they decide to raise the pension age. Perhaps some expected Syriza to turn Greece into Cuba or to print money without currency reserves. The left wing of Syriza would indeed want Greece to become something like Cuba. But would that make life easier for proletarians or would it be even more disastrous? I am pretty sure I am not saying something new here that Cognord would not have thought about already, so then, what is then the point of this criticism? What are its implications and what conclusions does it draw? I feel as if Cognord is more angered by Syriza politicians than he is angered by the fact that it is now clearer than ever that the suffering for workers, unemployed, poorer pensioners in Greece has no hope of abating even slightly, regardless of what any Greek politician will do, and also, which is worse, regardless of how much they struggle. Yes, we knew that demands were asystemic, but I think things are even worse. Even the most defensive and modest of demands are asystemic, which means a relentless and very rapid worsening of life, the scale of which is unprecedented. We imagined communisation as destructive, but now it seems that even the slightest struggle has a ‘scorched earth’ scenario hanging over its head.

There is also one inaccuracy, by the way, in the introductory paragraph of Cognord’s recent text with the reference to the ‘minimal Keynesian’ programme: Lapavitsas, a Syriza MP, called the Syriza programme ‘mild Keynesianism’ ever since before the elections (check out his BBC interview). It is pretty clear that Syriza is an inconsistent party anyhow, but I don’t think it helps the analysis to depict all of them as self-interested cynics who colluded with EZ politicians to impose more austerity on purpose. This is not because I am convinced they are good people, but because a personalising analysis would suggest that, if they were more honest, then better things would come. But this is blatantly not the case. If they were more honest, they would either not have gained power at all, or they would simply resign because their programme is impossible, and Samaras would be back in power. These were the options. You can call me ‘reformist’, but I would not want a return of the ND govt, until perhaps Syriza manages to become absolutely identical to it, i.e., a government of outspoken racists. And I think that the passing of the laws to grant citizenship to 2nd generation immigrants, and of civil partnership for gay couples, however measly and limited, have practical and symbolic importance for these groups in a context where racism and homophobia, including the scale of abuse, have been on the rise. Yes, all the options are really dark, but some are downright hellish. That is why I see no point in either cheering for and excusing Syriza or vilifying them.

The real question is, in my view, what are the options now for class struggle in Greece? Because it is now clear that no matter what struggles do they will be crushed by a combination of heavy policing and currency blackmail, which was already the case, but now it has all become far more blatant. It’s easy to vote ‘no’, but total economic collapse is frightening in reality, and not only for those in power. The response to the absence of money is mass looting, of course, but can this really go further, especially if it only takes place in one country? We have seen again and again how quickly and violently social order is restored after such outbreaks. The other response to lack of money is alternative currencies and solidarity economies. We know the limits of these also. The most depressing thing for me though is the lack of significant mobilisations anywhere else in Europe except Spain (and these under the Podemos banner, which might mean they are about to be weakened).

Ady Amatia

July 17 2015