Αναδημοσίευση του ομότιτλου άρθρου από τους New York Times (όπου υπάρχει και σύντομο σχετικό βίντεο):

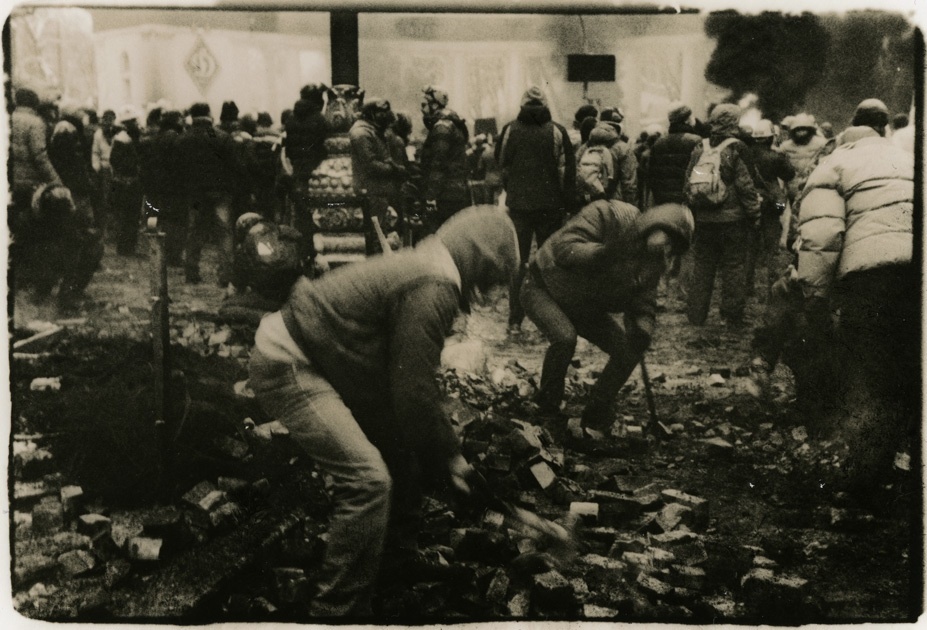

BEIRUT, Lebanon — Thousands of protesters streamed into downtown Beirut for a second day on Sunday to demand that the government resign over its inability to remove enormous heaps of garbage from the city’s streets. The demonstrations led to clashes with the police, who turned fire hoses and tear gas guns on the crowds.

At least 30 people were hurt, according to the Red Cross. Dozens of people were injured on Saturday, when the police also used rubber bullets.

On Sunday night, chaotic scenes unfolded as demonstrators refused to disperse and entered Martyrs’ Square, an expanse of empty space created by the destruction of Lebanon’s civil war a generation ago.

The garbage crisis has become the most glaring sign — at least to the senses of sight and smell — of the political paralysis that now grips the nation and has unified many Lebanese, usually divided by sect, religion and region, in what the protesters call the “You Stink” campaign.

Two more bags of trash were added to a mound of it near Floyd the Dog bar in Beirut. Garbage in the city has not been collected in over a week.Beirut Journal: Lebanese Seethe as Stinking Garbage Piles Grow in Beirut and BeyondJULY 27, 2015

The office of president has been vacant for more than a year, and Parliament essentially re-elected itself after being unable to agree on new elections, even as the country absorbed more than 1.2 million refugees from the Syrian civil war.

Fouad al Hassan, an actor known for his work in television comedies, said he took part in the protests outside the Grand Serail, the stately Ottoman-era building where Prime Minister Tammam Salam has his office, because “I want to change the system.”

“We want new blood or the country will stay the same,” added Mr. Hassan, 65. “Today, it’s too late for me, but I want it for my children. I want them to live a better life.”

Aline Shirfan, a 21-year-old civil engineer, said it was her first time participating in a demonstration. “I have nothing to lose, I’m so desperate,” she said. “If we don’t die from a bullet we will die from cancer from the trash smell.”

Men with covered faces threw stones at the police, but organizers of the You Stink campaign insisted that they were not part of it. In a telephone interview, Lucien Bourjeily, one of the organizers, described the men as infiltrators sent by “partisan elements” who were trying to tarnish a peaceful movement.

Martyrs’ Square was the site of huge rallies after the assassination of a former prime minister, Rafik Hariri, in a car bombing in Beirut in 2005. Those rallies eventually led to the withdrawal of Syrian troops and ended de facto Syrian control of the country, though Syria and the militant group Hezbollah, its Lebanese ally, denied any involvement in the assassination.

On Sunday night, clouds of tear gas reached Mr. Hariri’s tomb, which adjoins the Mohammed Al-Amin Mosque, which he financed. On a street leading to the Serail, traffic lights and shop windows had been smashed.

Before the violence on Sunday, Mr. Salam admitted at a news conference that “excessive force” had been used during the rallies on Saturday, and that the demonstrators had a legitimate grievance.

“What happened yesterday was the result of accumulating matters that have been building up and increasing the people’s suffering as the result of the vacuum we are living,” Mr. Salam said. He promised that he would hold government officials accountable and said, “I won’t cover anyone.”

Asked if he would resign, Mr. Salam said, “My patience is limited, and it’s linked to yours.”

For many years, Beirut’s trash and that of much of central Lebanon was sent to a landfill near Naimeh, a town south of the capital.

But the amount of trash long ago exceeded that landfill’s capacity, and communities nearby complained of the smell and blamed it for health problems. Protesters blocked the road to the landfill last summer, causing a pileup of garbage in Beirut.

They relented after the government promised to find alternatives. But when no alternatives materialized, the protesters blocked the road again last month, leading to the present crisis.

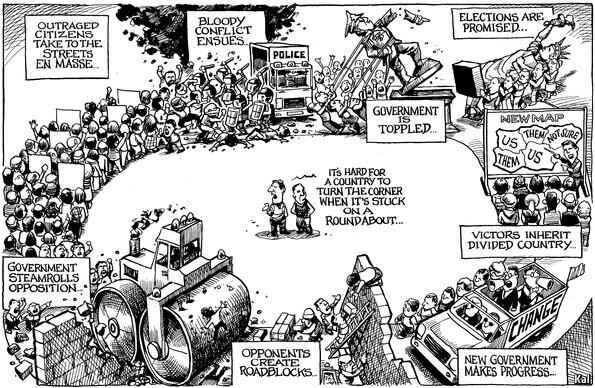

The complaints that brought ordinary citizens into the streets of Beirut over the weekend were not unlike the festering anger that prompted recent protests in Baghdad over the Iraqi government’s failure to provide enough electricity to power air-conditioners when temperatures soared well above 100 degrees Fahrenheit. In other countries, like Brazil, Honduras and Guatemala, largely leaderless protests have arisen suddenly and more or less spontaneously over allegations of government corruption and widespread perceptions of a lack of accountability.

On Sunday, some Lebanese who did not take part in the demonstrations expressed strong support for them. “Unfortunately, today is my shift so I can’t join. All my friends are already there,” said a woman who was working at a market and identified herself by her first name, Hiba. “This country is not functioning.”

As she was speaking, the electricity in the store went off. “Now you know what I mean,” she said.