Every major crisis forces social groups to come to grips with the deep contradictions of society. In capitalism, class confrontation is the prime mover that drives society forward : it forces the bourgeoisie to adapt to labour pressure, to “modernize”. Crisis is when these formerly positive pressures strain the social fabric and threaten to tear it apart.

Contradiction does not mean impossibility. Up to now, all big crises have ended in the system managing to pull through and eventually becoming more adaptable and protean. No “ultimate” crisis is automatically contained in even the most acute contradictions.

1 : Why “Civilization” ?

Capitalism is driven on by a social and productive dynamism, and by an un-heard-of regenerative ability, but it has this weakness: by its very strength, by the human energy and the technical power it sets into motion, it wears out what it exploits, and its productive intensity is only paralleled by its destructive potential, as proved by the first civilization crisis it went through in the 20th century.

No value judgement is implied here. We do not oppose civilized people to savages (even good or noble ones) or barbarians. We do not celebrate “great civilizations” which would have been witness to the progress of mankind. On the other hand, we do not use the word in the derogatory sense it has with writers like Charles Fourier, who called “civilization” a modern society plagued by poverty, trade, competition and the factory system. Neither do we refer to those huge geo-historical socio-cultural constructs known as Western, Judeo-Christian, Chinese or Islamic civilizations.

The civilization we speak of does not replace the notion of mode of production. It merely emphasizes the scope and depth of a world system that tends to be universal, and is also capable of disrupting and then reshaping all kinds of societies and ways of life. The hold of wage-labour and commodity over our life gives them a reality and dynamics that were unknown in the past. Capitalism today is the only all-encompassing network of social relationships able to expand geographically and, with the respective differences being considered, to impact on Djakarta as well as Vilnius. The spread of a world capitalist way of life is visible in similar consumer habits (McDonald’s) and architecture (skyscrapers), but has its deep cause in the dominance of value production, of productivity, of the capital-wage labour couple.

The concept of a mode of production is contemporary to capitalism. Whether or not Marx invented the phrase, it has become common since the 19th century because capitalism imposes on us the image of factors of production combined to beget a product or a service bought or sold on a market, and of a society ruled by supply/demand and productivity.

Then the concept was retrospectively applied (often inadequately) to other systems, past and present: the Asiatic or the domestic mode of production. (2) Whatever relevance these derivations have, they pay tribute to the overwhelming presence of the capitalist mode of production.

Capitalist civilization differs from empire, which has a heart, a core, and when the core withers and dies, the whole system around it goes too. On the contrary, capitalism is a polycentric world system with several rival hegemons, which carries on as a global network if one of the hegemons expires. There is no longer an inside and an outside as with Mesopotamian, Roman, Persian, Hapsburg or Chinese empires.

A crisis of civilization occurs when the tensions that formerly helped society to develop now threaten its foundations: they still hold but they are shaken up and their legitimacy is weakened.

As is well known, tension and conflict are a sign of health in a system that thrives on its own contradictions, but the situation changes when its main constituents overgrow like cancerous cells.

A century ago, capitalism experienced such a long crisis, of which the “1929 crisis” was but the climax, and capitalism only got out of it after 1945. Going back over that period will help understand ours.

2 : A European Civil War

At the end of the 19th century, capitalism as it existed was no longer viable, on both sides of the capital-labour “couple”: the productive forces of industry were too big to be managed by private owners, and the worker movement too powerful to be persistently denied a social and political role. Capitalism met the issue in a variety of ways. It did not turn “socialist” but it socialized itself, which took decades and included resistance, backlash and outright reaction. (Fascism was one of them, a forced top-down national socialization, as Stalinism was in a different way.) The evolution started with English trade-unionism in the late 19th century and culminated in the post-1945 consumer society.

Reaching that stage took no less than a European civil war.

14-18 and 39-45 were a lot more than inter-State conflicts, and their paroxysmal violence was not only caused by the extermination capacity of industry. The political and military hubris unleashed by WW II remains a mystery if we neglect the 1920s and 30s confrontation between a restless militant working class, and a bourgeoisie wavering between repression and integration, combining both without opting for the one or the other. Imperial Germany and then Weimar were perfect examples of this situation, but so were Britain where the bourgeois waged a class war in the 20s, especially against the miners, and the US, where unionization was de facto made impossible for millions of unskilled workers.

In 14-18, mutual slaughter came close to a self-destruction of the belligerents, at least until US intervention in 1917. Military illimitation illustrated the explosive power of the contradiction of a system dedicated to eliminate the remnants of the past, while trying to reunite in the trenches the classes of each country. 1918 hardly solved anything. The most advanced country, the US, exported its capital to Europe at the same time as it withdrew from the continent politically. Four outdated empires crumbled and parliamentary democracy went headway, but lacked the means to act as a social mediator. The two structuring classes of modern society remained stuck in a deadlock.

1917-39 broke down the international economy born at the end of the 19th century (the “first globalization”). It was a time of dislocation, of nationalist upsurge, of conflicts between and within States, with the creation of new nation-States without real “national” basis, for lack of a domestic market that could have helped create a people’s unity. (Two of them, Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia, would break up at the time of the “second globalization”). The mutual dependence of national economies on the world market is essential to capitalism (even the USSR was never totally walled-in), but this process is achieved with a succession and combination of openness (liberalism) and closure (Nazism and Stalinism). Amidst these fault lines, the 1929 crisis added more class collision.

In Germany, it was not the huge unemployment rate that caused the rise of the Nazis: it was the German situation as a whole since 1918. The 29 crash accelerated the ascension of Hitler by aggravating the political factors that had undermined Weimar since 1918. From 1930, the crash facilitated the advent of an authoritarian State, which ruled by government-decrees that deprived parliament of real power. It reduced the reformist capacity of the SPD and Centrum to next to nothing, marginalized the KPD even more, and increased the discrepancy between a democratic façade and a reactionary drift to the past, illustrated by the spread of völkisch nostalgiawhich conveyed a growing nationalist-racist mood and culture. (Unfortunately, idealists like Ernst Bloch were better equipped to understand this time-warp – when the past overlapped the present – than most materialists captive of a linear vision of history. (3) ) 1929 finally signified the disunity of Germany and called for political forces able to reunite the country (the classes) through violence. Fortunes were ruined and beliefs as well. A political vacuum had to be filled, and it was not be done peacefully. Up to 1929, “conservative revolution” remained a contradiction in words: in the 30s, the oxymoron became reality. As it militarized Germany, Nazism re-forged a forced people’s community closed-in on the German race. (4)

Nazi warfare was a head-on pursuit in an all-or-nothing fight, involving planned genocide and implying the final self-immolation of the country: the regime sacrificed German unity rather than yield to clearly superior enemies. When the Nazis engaged in military competition with three great powers at the same time, this was absurd from a pragmatic point of view, yet consistent with the Nazi rise to power and the logic of the regime. This was no Clausewitz-style war aiming to achieve a decisive superiority and stopping when that goal was reached: for Hitler, annihilating the Jews and enslaving the Poles and the Russians were a priority.

In both world conflagrations, Germany stood at the epicentre, with at its heart a heavy industry constricted by a geo-political framework which prevented it from exporting as much as its productive power required.

Various authors have suggested the idea of a “European civil war” from 1917 to 1945, but arch-conservatives, like Ernst Nolte, best emphasized the class undercurrent of that period because of their “class reaction” and political bias. (5) Whatever we think of the Russian revolution and its demise, the Bolsheviks’ seizure of power was a death threat to the bourgeoisie worldwide. It is impossible to understand Mussolini and Hitler if we forget the fear (combining facts and fantasy) of the working class among the bourgeois, a fear shared by a large part of the petit-bourgeois.

Although the working class never seriously tried to overthrow bourgeois rule in Western Europe after 1918, what mattered was that unions and socialist parties were perceived of as a challenge to be met. Fascism differed from the previous variants of reaction throughout the 19th century: it had roots in the industrial world, it drew in crowds, it praised technique as much as it eulogized tradition, in that sense it partook of modernity. Against fascism, Roosevelt and the Popular Fronts reunited the worker movement and those bourgeois ready to let labour play its part politically alongside capital. In that contest, the bureaucratized worker movement led by Stalinism was both an ally and a rival of the Western bourgeoisies. It was therefore logical that national resistance against German occupation should often take on an anti-bourgeois look and discourse against traditional elites associated with fascism, in Yugoslavia, in Greece, and in Italy where patriotic war, civil war and class war mingled against the Nazifascist enemy.

In 1939-45, instead of a proletariat v. bourgeoisie fight, but as a by-product of that previously inconclusive fight, three forms of capitalism confronted each other: the Russian bureaucratic statist version temporarily allied to the Anglo-Saxon liberal variant, against the German (and to a lesser extent Japanese) attempt to create self-sufficient empires.

After 1945, in Western Europe and Japan, parliamentarianism and the constitutional State finally fulfilled their function: to get a “people” together as a nation that integrated the labouring class. In 1943, a Tory politician, Quintin Hogg, said about the English workers: “We must give them reforms or they will give us revolution”. The phrase was excessive, yet meaningful.

1945 was to be different from 1918. At the end of WW I, the most powerful capitalist country stepped aside from European politics: the US refused to be part of the League of Nations and showed little interest in the rise of Nazi Germany. While Roosevelt was busy with the New Deal, he hardly cared about the war in Spain. In 1945, the two major powers, the US and USSR, did not just rule their own countries: each had the ability and the project to extend its domination over other parts of the world. Likewise, the bourgeois were not content with having the upper hand over the workers: the ruling class organized the capital-labour relation in such a way as to consolidate and perpetuate it.

3 : How Capitalism Globalized its Crisis of the 1960s and 70s

The post-45 “social peace” was limited to a few dominant countries, and even there “the affluent worker” was a myth. (6) Still, Western Europe developed various forms of Welfare State to pacify the toiling masses Q. Hogg was worried about, and heavily indebted governments (backed by US and Canadian credit) managed to produce the funding. An unspoken bargain was struck.

In the final decades of the 20th century, worker pressure destabilized this consolidation. Much is known about a crisis that started forty years ago. We will only make two points. The bourgeois managed to quell worker unrest in the 60s and 70s, but (a) did not address the real issue, and (b) the way this “victory” was won and its aftermath have led to more social unbalance. This § 3 analyzes point a. The following paragraphs will deal with point b.

In the early 1970s, capitalist production was running into its inevitable periodic predicament: over-accumulation creates a mass of value so large that capital is unable to valorize it at the same rate as before. The all-too visible forms of overcapacity and overproduction, not to mention the State “fiscal crisis”, revealed profit deceleration. (7)

Business re-engineering and globalization were supposed to have remedied that.

As the word suggests, globalization is perceived of as the creation of an open planetary market where investment, goods and people could (or should) freely move as they please.

This is deceptive.

Firstly, monopolies and oligopolies have not put an end to State rule, which is in fact getting stronger in terms of law and order, and protectionism is not over.

Secondly, what is the bottom line of globalization ?

Downsizing, casualization, substitution of individual contract to collective bargaining, outsourcing of manufacturing from one continent to another, promotion of the service sector at the expense of industry… all the 80s and 90s “re-structuring” was based on one privileged factor: the systematic lowering of labour costs.

Cutting down wages is a bourgeois constant. “The innermost secret soul of English capitalism [is] the forcing down of English wages to the level of the French and the Dutch. [..] Today, thanks to the competition on the world-market [..] we have advanced much further.” Marx quotes an English MP saying that “If China should become a great manufacturing country, I do not see how the manufacturing population of Europe could sustain the contest without descending to the level of their competitors.” Marx concludes : “The wished-for goal of English capital is no longer Continental wages but Chinese.” (Capital, vol. I, chap. 24, § 4)

Wages, however, though the most important variable in capitalism, are not the only one.

A remedy can prove worse than the cure.

Productivity gains were high again in the 1990s, especially in the US, thanks to computerization, the elimination of smokestack industries, and investment in low labour cost manufacturing in Asia. But, however much computers and containers help compress and transfer labour, they only patch up the causes of profit decline. All the critical features of the 70s are still here forty years later, masked by the profits reaped by a minority of firms and by the windfall profits in the finance sector.

The current huge technical changes, particularly the computerization of production and daily life, are misunderstood as a third “technological revolution” of comparable magnitude as those brought about by the steam engine in the early 19th century, and by electricity and the internal combustion engine late 19th-early 20th. This is forgetting that productive forces are not mere technical tools. By themselves, petrol and chemistry would not have been enough to generate an industrial expansion between 1870 and 1914, and Taylorism-Fordism was a lot more than the conveyor belt.

The social dilemma of the interwar period (intensive accumulation without mass consumption) had been resolved in the post-45 boom: intensive accumulation with mass consumption by transforming part of productivity gains into higher wages. In the aftermath of WW II, the US would export goods that differed from those then known in Europe, manufactured by another type of management, and harbingers of an innovative lifestyle. On the contrary, in the late 20th century, the Asian tigers and dragons, “New Industrial countries” as they were called, and now China, all too quickly labelled “the workshop of the world”, make the most of existing techniques and manufacture the same objects as those made in the West, albeit at a lower cost. As supply exceeds demand, prices are pressed down… so are profits. The “long decline” that started in the mid-1970s has been compensated for but left unsolved. A new accumulation phase would imply more than technology, and require no less than the launching of new forms of production and labour, in other words a different regime of accumulation and a a different mode of regulation. On the contrary, emerging economies rely on a neo-Taylorism without Fordism. (8)

The bourgeoisie has tried once more to short-circuit its partner-opponent by a roundabout technological fix, this time by a leap forward in MTC (Means of Transport & Communication): this is as successful as dosed-up growth can last.

Moreover, Chinese economy is not self-centred and at present no indicators show it is going to cease being over-dependent on exports.

Besides, as it is transferred from the old industrial metropolises to Asia, labour gets organized, presses demands, and wage rises in China start forcing companies to invest in countries with a supposedly more docile workforce.

Globalizing a problem is not enough to solve it. Internal production costs, as well as external and social costs (to remedy environmental damage) cannot be made up for by in-firm productivity gains, especially in countries which have opted for a service economy. The profitability revolution formerly experienced in agriculture and industry will never be on the same scale in the service sector: some of it is ideal for standardization (telecommunications), some is not (health care).

There is no need to dwell on the fact that since 2008, the ruling classes have treated the crisis by means that perpetuate it. Lowering labour income for the sake of reducing companies’ and governments’ deficit, and injecting more cash into banks, will not address the basic issue: insufficient value creation and investment, which no expanding trade can compensate, particularly an expansion souped-up by credit. The bourgeoisie is going the opposite way of what helped come out of the 30s Depression: demand support, public regulation, long-term investment.

So, if capitalism did make a fresh start at the fall of the 20th century, its victory was not what it seemed. The current crisis reveals that the 80s and 90s boom did not overcome the 1970s predicament: overcapacity, overproduction, overaccumulation, declining profitability. The worldwide growth of the last thirty years is undeniable and unsound. Its success is based on causes that contradict the system’s logic: capitalism cannot durably treat labour only as a cost to be reduced at all costs, prioritize the financial sector, live on debt, nor extend the American way of life on all continents. Each Earthling, or even a couple of billions, will not possess his own car, pool and watered lawn.

4 : Neo-Liberalism Fallacy

While each of us is personally encouraged to live on credit, States are increasingly supposed to be run on the « prudent man » principle of responsible management: “Let’s not spend more public money than we have”.

In fact, late 20th century neo-liberalism had little in common with 19th century liberalism, when the bourgeois used to cut down on public expenditure, arguing that those sums would deplete their own hard-earned money and decrease investment. The role of the State and its budget were to be kept to a minimum.

This is not at all what Thatcher and Reagan initiated. When they increased public spending by debt financing, it did not help resolve the fiscal crisis of the State, nor was it that policy’s goal : its dual purpose was to reduce the tax levy on companies, and to reduce labour ability to put pressure on profits. Privatizing and deregulating industry and banking (a process inaugurated in the US by J. Carter and continued by B. Clinton after 1993) aimed at shattering the institutional framework which provided labour with means to defend itself (the famous “Fordist compromise”). Neo-liberalism was doing away with mediations that gave a little individual and collective protection from market forces.

This had to occur at the core of the system: manufacturing, transport, energy, namely sectors which were (and still are) vital and where worker organization and unrest were the greatest. So the attack naturally targeted large factory and steel workers, miners, dockers, air traffic controllers… As those key sectors were defeated, finance took the opportunity to push for its own interest at the expense of industry: this was a side-effect of the evolution, not its cause.

The rise of Asia was another consequence of labour defeat. US, European and Japanese bourgeois started having products manufactured in Asia or Latin America, then opened their markets to Chinese imports, only after having crushed worker militancy in their own countries.

5 : Wages, Price & Profit

A Niagara of articles are being written to explain how the bourgeois (usually called the rich) have been stealing from the poor for the last decades. Quite true, but the relevant question is whetherafter 1980, the bourgeois counter-attack on labour was successful… or too much so. Systematic negation of the role of labour (i.e. systematic downsizing manpower and cutting down labour costs) brings profits in the short term, but proves detrimental in the long run. Global growth figures of world trade and production in the last thirty years obscure the essential: there are still not enough profits to go round. Faster capital circulation does not necessarily coincide with better profits. In 2004, a number of French companies increased their yearly profits by 55%, mainly because they freed themselves of their own less rewarding sectors. The question is how far insufficient profitability can be compensated by a strategy that benefits a minority entrenched in strategic niches (the expanding hi-tech business, companies with strong links to public spending, and last but not least finance). There is nothing new here. What was called the mixed economy or State monopoly capitalism in the 1950-80 period also relied on a constant transfer of money from business as a whole to a happy few companies. (9) But the running of such a system implied a modicum of dynamism: the most powerful firms would have been unable to take more than their share of profits if overall profitability had been lacking.

Capitalism is not simply an accumulation of money at one pole (capital) and an outright lowering of costs on the other (labour). And even less so an accumulation of speculative windfall profits made at the expense of the “real” economy, i.e. companies that make and sell items (be they mobile phones or on-line bought films). Capitalism cannot be just money sold for money.

From the mid-19th century onwards, capital has always had to take labour into account, even under Stalin and Hitler. (10) If there is one lesson to be learned from Keynes, it is that labour is both a cost and an investment.

There is a limit to what capitalism can exclude without reaching a highly critical stage: in a world where the economy and work reign, the continuity and stability of the existing social order depends on its ability to put at least a fair amount of proletarians to productive work.

Productive in more than one sense: productive of value for companies to accumulate and invest; productive of wealth for the ruling classes and of money for taxes; productive of what is needed for the upkeep and reproduction of the dispossessed as a distinct group and a pool of potential labour; productive of the necessary maintenance of what remains of other classes; and productive of “meaning”, of collective ideas, images and myths capable of getting classes together and taking them along towards some common goal: a society, and this applies to capitalist society as well, is not an addition of passive workers and atomized consumers.

The nexus here is how much capital’s treatment of labour affects the reproduction of society. The renewal of the labour force has to be global, both social and political.

On the contrary, re-engineering has been functioning since the 1980s as if labour was open to ruthless exploitation. Manpower looks inexhaustible (bosses can always hope replace insubordinate or aging proletarians by fresh ones), yet it is not.

In 19th century European factories (as in many factories in the emerging countries today), the bourgeois would exploit the worker until he wore out. This brought in lots of profits for years, but when the army called up millions of adult males in 1914, the military realized that the lower classes were plagued by malnutrition, morbidity, rickets and disability. It is fine for the individual boss to care only about the value produced in his company. Bosses as a class have to take into account the reproduction of the labouring class. Misery and profit do not always get on well: labour is often more productive when he is better paid, housed, fed, kept in good health and even treated with a modicum of respect.

Socially, “rich” countries have abandoned their poorest 20% (the bottom fifth) to their dismal fate. The relative part of wage-labour in national income has gone down (sometimes by 10%) in the US and in most old industrial countries. Millions of young adults live in poverty, there are more and more working poor and new poor, blue collar and petty office workers (60% of the working population in France) are being levelled down, etc., yet upper class victory has its price. The drive to ultra-productivity causes work stress, loss of working hours and other expenses, the burden of which ultimately weighs on collective capital. Likewise, cutting down the “social” wage is short-sighted policy: money spent on education, health and pension is an investment which benefits capital’s cycle. Too much cost-cutting has brought in quick profits, but the incidental expenses of globalization will have to be paid for.

The more and more unequal sharing of profits between capital and labour is one aspect of a lack of profitability, caused not by the greed of financiers (the bourgeois are no more or less greedy today than yesterday), but by the shortage of profits gained in industry and commerce. If one leaves the US aside, “the world economy proves incapable of sustaining a demand that would keep its productive (and particularly) industrial capacities busy”. This was the point made in 2005 by a French economist with no Marxist or leftist leanings, Jean-Luc Gréau. (11) He argued that the systematic worldwide lowering of labour costs is part of the problem, not the solution: “How do economists manage to publicly ignore the effects of wage deflation on the world situation ? [..] Wage deflation means deflation of value creation.”

As mass consumption is now a cornerstone of capitalism, systematic downsizing and outsourcing finally lower the purchasing power of wage-earners and unemployed. Far from being a mere fiction, money is substantified labour, and the relevance of money derives from the living labour that it represents. When labour is degraded, neither rich nor poor can endlessly buy on hire purchase, and sooner or later the debt economy meets its limits. Under-consumption is an effect, not a cause, but it intensifies the crisis.

Politically, the bourgeoisie needs workers who work and who keep quiet when they are out of work. As long as wage-labour exists, there will never be enough work for everyone. But there has to be enough of it for society to remain stable, or at least manageable.

Capitalism’s logic has never been to include everyone as a capitalist or wage-earner, nor to turn the whole planet into middle class suburbia. Nevertheless, capital-labour relations necessitate some balance between development and underdevelopment, wealth and poverty, official and unofficial labour, job security and casual work, stability and flexibility. Otherwise, the privileged residents from suburbia will be afraid to go shopping downtown at the risk of being met by underclass gangs, muggers or looters. Too many gated communities coexisting with too many slums make a socially explosive cocktail. A society cannot be pacified only by police.

In order to reproduce itself, capitalism must not only feed and house the wage-worker, but reproduce what constitutes his life, his family, education, health, etc., therefore the whole of daily life. The supposedly normal course of capitalism is far from peaceful, and social tensions are different in Turino, 2000, from Manchester, 1850: food riots are rarely to be seen in “rich” countries now, though millions of US citizens have to eat on food stamps. Poverty and want change with the times. If contemporary daily life has been successfully turned into a succession of purchases (millions of people trade on eBay and similar sites), that does not prevent the repetition of riots in the old capitalist centres as in the new ones. Looting is not revolution, but when the poor take to the streets to go looting, as in London, 2011, it shows the market unleashes forces it cannot control.

When the bourgeois wonder how to bring back solvability not only to large masses, but to whole countries, it is because the wage relation runs the risk of not adequately providing conditions for social reproduction any more.

6 : The Impossibility of Reducing Everything to Time

When driven to extremes, the permanent search for time-saving becomes counter-productive. Shortening time results in everything being treated short-time. In 1960, the success of the American way of life was proved by its ability to convince the motorist to buy a new car model every two years: fifty years later, our home computer recommends we update our software every odd week. Built-in obsolescence conflicts with sustainable growth and renewable energy: the essence of time is that it can neither be stored nor renewed.

There comes a point where social pressures no longer drive the system forward, but strain it. What previously made it strong – to separate, quantify and circulate everything at maximum possible speed – turns against it.

Time is a contemporary obsession, at work, at home, in the street, everywhere. When companies try to produce and circulate everything in real time, what they are really aiming at is zero time. Modern man cannot bear to be doing only one thing at a time. A Martian visitor might think we manufacture and consume not so much objects as speed. Competition forces each firm to minimize labour costs, and each worker’s contribution is to be counted in time – however debatable the resulting figure will be. Computers and experts are there to economize time, to absorb it, eventually to nullify it: “Time & space don’t exist any more”, says your HP Photosmart printer CD. Yet this never goes fast enough to make time profitable enough.

Capitalism always proves at its best in the short term, but nowadays it lacks some vision of the future and some public regulation that only work in long time-frames.

7 : A Class Outof Joint

When he is left to himself, the bourgeois seeks his own maximum profit, and follows his natural inclination to combine technical prowess with money grabbing.

One of his recent favourite ways has been to promote the domination of interest-bearing capital over industrial and commercial capital.

Since the Industrial Revolution, hypertrophied finance has usually been a sign of capital overdrive. Low break-even point in manufacturing and trade spawns a tendency to seek higher capital efficiency in money circulation, which inevitably results in crude and sophisticated speculation. This works fine – as long as it lasts – for the happy few in Wall Street and the City, but results in an imbalance between the various bourgeois strata.

There is a connection between labour’s defeat at the end of the 1970s, and the shake-outs which have occurred in finance since. Financial freewheeling is one of capital’s preferred methods of negating what creates it: labour. Credit means spending the money one does not have but hopes to get, for instance by turning the (expected) rise of one’s house on the property market into an increased borrowing capacity. Money however is not endowed with an endless power of self-creation: it only makes the world go round in so far as it is crystallized labour. Financial crash is a reality-check: between labour and capital, the cause and effect relation is not what the bourgeois would like to think. Labour sets capital (and money) into motion, not the other way round.

Speculation is a natural, and indeed indispensable feature of capitalism: over-speculation heralds financial storms.

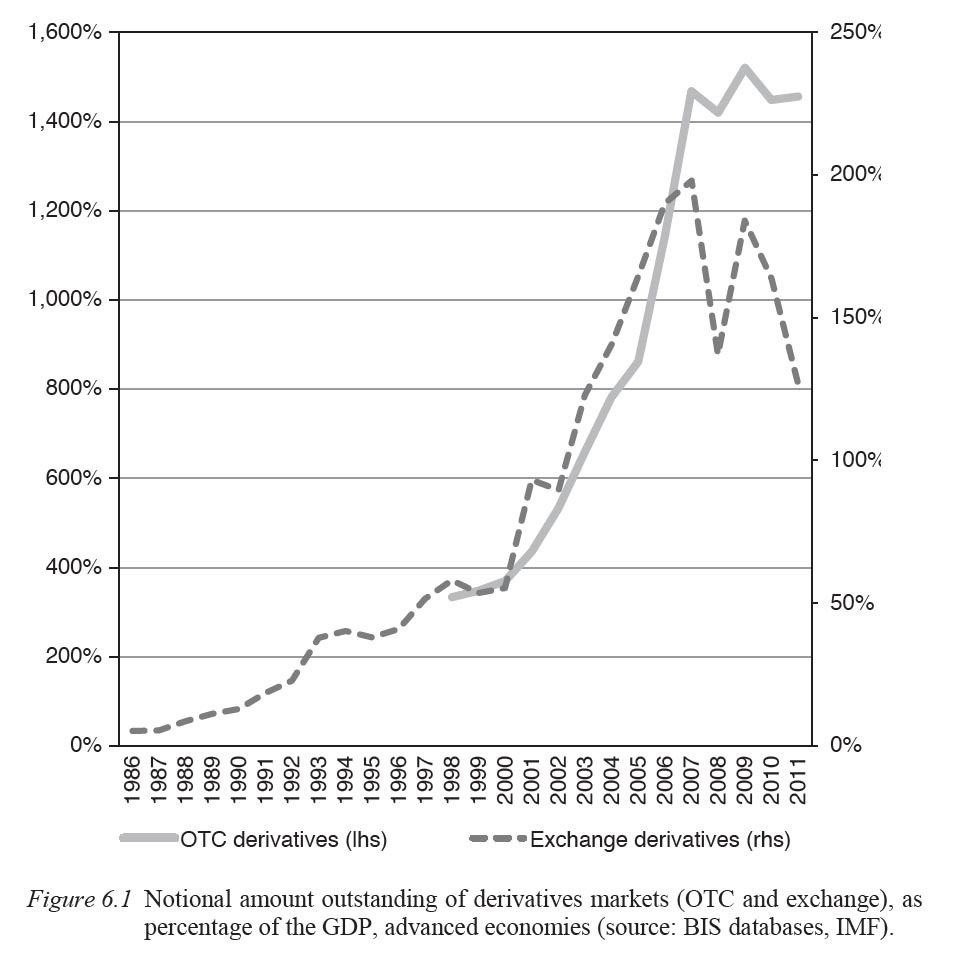

As class struggle turned in favour of the bourgeois after 1980, they took maximum advantage of the situation, of course at the expense of the proletarians, but also with a power shift within the ruling class, and the rise of financial capitalists exacting two-figure profits when industrial profit rarely exceeds 3-4% per year in the long run. Rent, formerly surplus profits obtained by monopolising the access to resources or technologies, has tended to become the dominant form of bourgeois income: securitization (transforming debt into commodities), derivative markets (literally selling and buying the future: insurance, options, risks, derived from existing assets), speculation on commodities, speculative bubbles (particularly on the property market), stock options, etc. Hi-tech and cyber-economy revive a rentier class Keynes wished to see euthanized in the interest of the system as a whole. Financial escalation and unprecedented money creation by banks are too well known for us to go into any detail here.

Some synergy must be found between financier and engineer, shareholder and manager. Share prices are not the only yardstick for deciding the optimum cost/benefit ratio. Financial products are as “real” as ironmongery, but only in so far as they are developed in parallel to manufactured and sold objects and services which are more than mere money flows.

All bourgeois share a common position as a class. It is the would-be reformers (often repentant intellectuals familiar with the corridors of power, like J. Stiglitz, policy maker in the World Bank and the Clinton administration) who theorize the “real” economy and hope to enrol true entrepreneurs in opposition to money-makers. The bourgeois are divided but stand as one against labour to defend their interlaced interests. There was no cohesion in the German ruling class in the 1920s, until it rallied behind Hitler. A lot will depend on whether financial, industrial and commercial sectors will remain disunited, or converge on a policy of reform – not the case so far.

8 : The Money God that Fails

When the worker struggles of the 60s-70s were contained, unchecked capitalism acted as if it was free to capitalize everything, the air we breathe, the human genome or the Rialto bridge. Anything is liable to become an adjunct to value production or an object of commerce.

Though this trend to universal commoditization is more proof of capital’s omnipresence, capitalism cannot do with an entirely capitalized society: it needs institutions and norms that are subordinate to it, but it also needs them not to directly comply with the profit imperative. Schools are not supposed to add value to a capital. Civil servants are not business men. “Research & Development” requires basic research. Accounting requires trustworthy figures. The same company which fiddles its own book expects to be provided with honest government statistics. Public services have to submit to capitalist standards and yet retain a certain degree of autonomy.

If the limits of homo economicus are now being debated, if Karl Polanyi and his critique (The Great Transformation, published in 1944) of the illusion of a self-regulating market become fashionable, it shows that even the liberals have to admit the necessity of restraining the grip of profit-making over society. Polanyi contended that the human propensity towards the market was historical, not natural: capitalism had disembedded the production of the means of existence from both social life and nature. No Marxist and certainly not a communist, Polanyi was not opposed to the existence of a market: his remedy to the autonomization of the economy was to re-embed productive activity within mutual links. Written in the aftermath of the Great Depression, this critique coincided with a capitalist effort to regulate market forces. In the last decades, there has been a renewed interest in Polanyi’s emphasis on “embeddedness”: reformers would like the economy to be brought under social control, in order to create a sustainable relationship with nature..

Polanyi had a point : individualist money exchange erodes the social fabric. He only failed to see that we cannot expect capitalism to limit itself: the market always tends to over-develop. As the liberals are right to point out, the advantages of capitalism come with its defects. In the colleges where The Great Transformation is taught, managers dream of tying teacher pay to students’ performance on standardized tests. Polanyi was a naïve believer in the self-critique of capitalism.

9 : Quantifying the Qualitative (When the disease becomes the medicine)

How does a system based on universal measuring react to excess quantitativism ? By quantifying quality. You can now do a Ph.D. in Happiness Studies : Gross Domestic Product is fine when complemented by Gross National Happiness.

At a time when the West doubts its own values and looks to the East for soul food, it is not by chance that GNH originated in Bhutan, the first country where it was first officially used. The concept was not born out of pure tradition: it was invented by the local rulers when Bhutan was going through a modernization process – a code phrase for entering the capitalist age. GNH was to act as a bridge between mercantile pressures and the prevailing Buddhist mind-set, and to provide Bhutanese society with an ideology presenting wage-labour and a money economy as suited to the well-being of people. Similar surveys followed in “modern” countries, and opinion polls now collect data on wellbeing. (12)

It is a well-known sociological “law” that in a survey the questions determine the answers : the sophisticated indicators used in interviews to measure the population’s well-being served to hammer into Bhutanese heads the idea that Bhutan’s evolution was good for them.

GNH is as manipulative as GDP, but also equally deceptive for its users, be they experts or the rulers that pay the experts. While it claims to be a guide to proper planning for the future, and to be taking into account non-strictly economic factors, GNH works with the same logic as value: it puts everything together, from the water-table to girl school attendance, and synthesizes it (or pretends to) in order to reach figures and graphs that bring down reality to common features. Applying econometrics to daily life cannot compensate for the lack of a general vision that the present competing world of States and companies is by its nature incapable of achieving, as everybody actually knows. It is an open secret that GNH compilations scarcely help upgrade sustainable development, cultural integrity, ecosystem conservation, and good governance. But never mind. As GNH fails to quantify well-being and happiness, new constructs see the light of day, like the Genuine Progress Indicator. As mental health does not suffice, emotional health is now deemed metrically measurable. When factual data prove inadequate, specialists compile memories. Whenwellness falls short of required norms, a long list of various wellnesses is made up, and new papers are written.

The figure society is also a report society. In 2005, the United Nations sponsored a Millennium Environment Assessment project, to evaluate nature according to what it gives us, and to know the cost if we lost it: its contribution for 1982-2002 was estimated at $180,000 billion. The figure has been contested, which requires more MEA studies. Productivism may be discredited in manufacturing, not in research.

Happiness teachers are the contemporary lay preachers that patch up the inadequacies and monstrosities of present times. It is quite natural that Happiness research should obey the reductionist figure-obsessed logic that prevails in intellectual and political life, or in education, where school-kids are assessed by box-ticking: we are all benchmarked now. Tellingly, this is not what critics object to. They denounce the fact that governments define GNH as it suits them: isn’t that the case with all statistics ? They deplore the un-scientific criteria : how could well-being fit in with any objective standard ? Only a scientistic mind can regard happiness as an object of science, or emotion as an analog to economic progress. They bemoan the national bias, but it was inevitable Bhutan should find comfort in its own version of GNH. A 21st century US GNH would validate the American way of life as the US likes to picture itself now, a multi-cultural, eco-conscious, minority-friendly society, certainly not as it was in 1950.

GNH is a product of a time when a GDP-led world is in crisis, and deals ideologically with its crisis. Zen wisdom goes well with GNH.

10 : Forbidden Planet ?

A system bent on treating labour as an infinitely exploitable asset acts the same with nature. As early as the 50s and 60s, far-sighted observers warned about ecological risks. (13) Yet, as a whole, post-1980 growth has meant more production, more energy (including nuclear energy) consumption, and more planned obsolescence.

A capitalist contradiction has become more visible and more acute than a century ago: if this mode of production is bound to commoditize everything, this process includes its environment (“nature”), which can never be completely turned into commodities. It is economically sound for a fridge or a video-on-demand to be indefinitely interchangeable and renewable. The same logic does not apply to trees, fish, water or fossil fuels. It is going to be harder to do something about CO 2 than it was in the 1930s to remedy the damage done by the dust bowl. Even if the US benefits from shale oil and shale gas (which remains to be seen), for most countries the cost of fossil energy will continue to rise and become increasingly uneconomical, which does not mean that this will block the system: there is always a way out of a severe profitability dilemma, a calamitous way.

Capitalism must find some balance between itself and what it feeds on, with its social as well as natural environment: “nature” is one of those indispensable not-to-be-fully capitalized elements.

What is involved here is first the wage versus profit issue, but also everything it implies. Company, wage-labour and commodity are indeed the heart of the system, but that heart only beats by pumping what fuels it, mankind and first of all labour power, and also nature.

One does not have to be an ecological catastrophist to realize the contrast between the beginning of the 21st century and the situation in 1850 or 1920. A huge difference with the 1914-45 crisis is that accumulation now meets ecological limits as well as social ones: overexploitation of fossil fuels, overurbanization, overuse of water, climate risks… combine so that the mode of production uses up its natural capital, while the decline of Keynesianism deprives the State of its former regulating capacities.

When private market forces are no longer checked by public counter-power, capital’s inherent illimitation is given free rein. Deregulation, privatization and commercialization have contributed to deplete natural conditions which cannot be infinitely renewed. In 50 years, chemistry and agribusiness have multiplied by 4 or 5 the yield of wheat-growing land… providing the farmer inputs 10 calories to get an output of 1. The day capital has to factor in all the elements necessary to production, overexploitation will start becoming economically unprofitable.

Up to now, business could regard energy inputs, raw materials and environment as expendable sources of wealth which were taken for granted. As long as the cost of water pollution by the aluminium factory for the rest of society would not be paid for by either the producers or buyers, business could ignore it. Such a “negative externality” must now be integrated into production costs: this, capital finds difficult to do, and so far there has been less action than talk, with “systems thinking” and “systemic approach” becoming buzz words. “De-growth”, “un-growth” or “zero growth” are incompatible with a system that still relies on mass manufacturing and buying of big (cars) or small (e-readers) items, planned obsolescence, and huge coal-fired or nuclear power stations. Smartphone is as much productivist as the Cadillac car.

Ecology is now part of ruling class ideology. It has even given birth to a new popular genre: doomsaying, which in true religious fashion thrives on fear and guilt: the fault lies in human acquisitiveness, in our ingrained materialistic foolish hedonism.

Yet the world is not determined by the opposition between man and nature, between technique and nature, between a destructive megamachine and the continuation of life. The biosphere is indeed one of the limits against which capitalism collides, but the connection between the human species and the biosphere is mediated by social relations. The “nature” we are talking about is not exterior to the present mode of production: raw materials and energy are part of the framework whereby labour produces capital.

Electricity, for instance (a form and not a source of energy), perfectly suits capitalism: it exists as a mere flow that is not easy to store, and therefore must keep on circulating. If its production costs happen to exceed its benefit, what can business do except passing on the buck to the State, but where does public money come from ? We are faced with the paradox of an amazingly mobile and adaptable system that has gradually built itself on an increasingly non-reproducible material basis.

Human, social and natural ability to adapt, for better or worse, are certainly larger than we think. Soon we might have to get used to living in a highly dangerous environment. The Japanese start to wonder what is worse for a child : having to play in an irradiated playground environment, or be banned from outdoor playing ? Nuclear power creates a situation when capitalist investment could stop being profitable. For its own reproduction, a social system feeds on (human and natural) energy and raw materials. If a system spends more resources ( = money) on preserving its environmental conditions than it is getting out of them, if the social input exceeds the social output, society breaks down.

As present society is unable to address the issue on anything like the scale necessary, two options combine: mild accommodation, and playing the sorcerer’s apprentice. Science, business and government are currently cooking up imaginative and (allegedly) profitable geo-engineering solutions : removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and depositing it elsewhere (like “advanced” countries shipping their industrial toxic waste to Africa), managing solar radiation to cool the planet by reflecting radiation into space, fertilising oceans with iron, brightening clouds, etc. If climate goes wrong, let’s have weather control, and if industry puts the environment at risk, let’s change nature. (14)

Dodging the obstacle by the same means that create it : one wonders which is worse, the failure or success of such science-fictional projects.

11 : No Capitalist Self-Reform

There is no shortage of lucid perceptive minds in capitalism. Indeed, some of its early theoreticians suggested restraint (A. Smith) or reforms (Sismondi). (15) Nevertheless, such moderating influence fell on deaf ears, unless it was backed by mass action, strike, riot, Chartism, the Paris Commune, fear of revolution, or in the US the violence narrated by Louis Adamic’s Dynamite (1931). It always takes more than books and speeches for a class to realize where its long-term interest lies.

Only organized labour forced doses of regulation upon reluctant bourgeois: no New Deal without the sit-down strikes.

On the contrary, in the ebb of struggles, freewheeling capitalism acts as if it could make the most money out of anything.

Today, the more data are collected, the more sophisticated software and applied maths become (high frequency trading), the less self-control there seems to be. A case in point is the reluctance to separate investment from commercial banking, as compared to the scope of the Glass-Steagall Act in 1933. Instead, the rulers look for more control over work and over the people. Neo-liberalism never minds government when government deals with law and order, and it is quite compatible with bureaucracy. Laws, regulations, guidelines, protocols and codes of ethicshave proliferated with the computerized standardization of every domain from medical care to education or the stock exchange. The precautionary principle is hyped by the same society that keeps playing with fire (nuclear risk being just one example). Potentially unhealthy industrialized food is served by glove-wearing shop-assistants. The consensus is that the more information we read on packets or on the web, the safer we are. The “Knowing Is Doing” fallacy is typical of a world in disarray.

Self-control has never been capitalism’s strong point. The bourgeois excels in making use of human and natural resources to produce and accumulate but, despite thousands of think-tanks, he is unable to think of capitalism as a totality because it is not his business, literary. When a company invests in a factory or a mine, the managers make the most of manpower, raw materials and technology, and only take care of the rest (occupational accidents, toxic waste, water pollution, etc.) if and when they come under pressure from the work force, law, local authority or whistle blowers. Bourgeois priority is to increase the productivity of labour and capital: that is what they are bourgeois for and they prove good at it. Long-term and “holistic” thinking come second.

Paradoxically, the abundance of reform “road maps” is a sign of procrastination. Most schemes conform to the current tendency of increased individualization. Whenever the possibility of higher direct or social wage is raised, it is usually conditioned on the wage-labourer personally submitting to overtime, compulsory re-training, a private insurance policy, etc. This is neglecting the fact that a social compact is only viable if it is collectively entered into and respected: in other words, collective bargaining. Yet the bourgeoisie persists in treating society as an addition of single atoms free to associate or stay apart. Historical replies to social questions cannot be individual.

Capitalist challenge nowadays is to make labour more profitable, and also to restore a working balance between accumulation and natural conditions. The ruling classes are evading both issues.

European politics is a clear illustration of this. The rush to unity almost immediately followed the proletarian defeat of the 1970s. At the same time as China was busy accumulating dollars thanks to the US trade deficit, the euro was born. This single currency was groundless: it did not come out of any socio-economic, let alone political, coherence. What is sometimes called the biggest single world market is nothing more: the European Union is a 500 million-strong market devoid of common purpose and political leadership. Nation-building took centuries in Europe. State is now declared outmoded, whereas trade is regarded as a pacifier, equalizer and unifier. A single currency has been imposed upon unequal, rival and still national economies, as if Greece could quietly coexist with Germany (2/3 of German trade surplus comes from the euro-zone), while the European budget is a trifling amount compared to the US federal budget. This is tantamount to diluting the social question by extending it over a larger and larger geographic area.

12 : Deadlock

The proletarians are not just victims of capitalist contradictions: their resistance deepens these contradictions. Chinese workers put forward wage claims. Thousands of miles away, Accor hotel cleaners fight for better working conditions. Even when defeated, and it often is, labour unrest aggravates the crisis, and contributes to a social stalemate in which up to now all classes take part, as between the two world wars.

Unlike the 30s, however, no New Deal is in sight. Far-reaching reform is impossible without a large deep social movement: deprived of mass pressure on the shopfloor and in the street, reformers remain powerless.

In the mid-20th century, in spite and because of proletarian defeats, the labour/capital confrontation finally entailed an adjustment of the exploitation of labour and began to regulate itself, with the “capital + labour + State” association.

Today, opposed classes counteract each other without any reformist nor (yet) revolutionary prospect. Up to now, capital disrupts and breaks apart labour far more than labour practically challenges its own reality. As we will see in the next chapter, few acts could qualify as anti-work or anti-proletarian.

Though the past is never re-enacted, the inter-war period offered a not too dissimilar picture, with the bourgeoisie proving unable to reform capitalism and the working class unable to overthrow it, until political and military violence unblocked the historical evolution.

As recalled in § 2, three forms of capitalism coexisted and fought in the 30s and 40s: a “market” type led by the US and Britain; a “State bureaucratic” type in the USSR; and a German very different but also State-managed type, where under Nazi rule the bourgeois kept their property and wealth but lost political leadership.

We now know what happened in 1945 and later in 1989, but in 1930 or 1950 very few (bourgeois or revolutionaries) were able to tell how it would all unfold. It is easy to explain today why the variant most adequate to the inner nature of capitalism would come out as the winner, but the other variants proved fairly resilient, to say the least. The vagaries of 20th century class struggle brought the unexpected: though they were indeed capitalist (and it was essential for radical critique to be clear on that issue, as it still is now), Stalinism and Nazism did not fit well with capitalism as communist theory was able to understand it at the time.

Because the State absorbs and concentrates society’s potential violence, intra- and inter-State contradictions, far from being neutralized, generate multiple tensions and conflicts, including those now called ethnic. Contemporary globalization inevitably comes with the prospects of war. The 1914-45 era reminds us that in the absence of revolution, disorder and cataclysm can throw a social system into turmoil without terminating it.

13 : No « Creative Destruction »… Yet

All the components of the crisis we have summed up refer to the degree of exploitation, to the relation between the two classes that structure the modern world.

When labour pressure is unable to moderate private capital and influence public policy, wages tend to go down, consumption to rely on hire-purchase, finance to dominate industry, privatization to develop at the expense of public services, money to colonize society, the market to evade regulation and short-termism to prevail over long term investment and planning. In Victorian days, later at the end of the 19th century, and then after the 1917-45 European civil war, each time worker unrest, in spite of its non-revolutionary character, threatened profits, until it forced the bourgeois into better adapted forms of exploitation. Labour countervailing action periodically drives capital forward and both softens and worsens its domination: “taming” capital reinforces it.

The transition from Keynesian-Fordist national compromise to globalized unbridled bourgeois rule resulted from a shift in the social balance of power. After 1945, the business-union-State settlement depended on the ability of labour to impose some form of deal. The 1960s-70s struggles put an end to give-and-take. The ruling class won.

Today’s class struggle in the West combines labour resistance and bourgeois refusal to give up even a portion of its vested interests. The interlocking of the two forces results in a stalemate than cannot go on for ever.

Capital has acted as if it could disintegrate labour, or even obliterate it, as bluntly put by professor M. Hammer in 1990, whereas labour is the stuff capital is made of. It is sound capitalist strategy to lower the cost of labour in Denver by having local workers buy cheaper imported goods. This is what Britain did in 1846 with the repeal of Corn Laws that limited food imports : cheaper bread reduced labour’s cost of life, hence wages. But when US capital gives Denver labour the strictest minimum pay to buy mainly made in China goods, there is a flaw: what will be manufactured in Denver, and what to do with the local proles ? Not everyone has the chance to become a computer specialist, nor the ability to live on diminishing social benefits: will work in the future be (in the best of cases) casual, or (more likely) a succession of menial odd jobs and periods on the dole ? Bourgeois answer is yes : there will remain a lot of unemployed and working poor in Denver for quite a while, but it does not matter because they can still eat junk food and afford Asia-made cell phones. It is logical, but the logic is warped.

Prioritizing global over local, un-coupling the wage-worker income from the society and the market where he lives, would be feasible if labour was as flexible, fluid, separable and expandable as figures, indeed… as money, i.e. a substance that is transferable, interchangeable and dispensable with at will. And this precisely is the capitalist dream. The present condition of the world and the current crisis prove how strong this utopia is, and how wrong: virtuality is a fallacy. The “real” economy may not be as tangible as it seems, but it has a degree of reality which the financial universe is lacking. On can play with money, “liquefy” banks and launch credit lines at will for years. On the contrary, labour is neither virtual nor virtualizable.

Capitalism never overcomes its contradictions: it shifts them, adapts them to its logic while adapting itself to them.

“Capitalist production seeks continually to overcome these immanent barriers, but overcomes them only by means which again place these barriers in its way and on a more formidable scale.” (Capital, vol. III, chap. 15)

Capitalism is based on its ability to provide wage-labour with means of existence. It can keep going with billions of people starving, as long as the core – value production – perpetuates itself on a constantly enlarged scale (as required by competitive dynamics : today Shanghai is part of the centre of the system as much as Berlin). Manchester was prosperous while “the bones of cotton-weavers [were] bleaching the plains of India”, as the Governor General of India wrote in 1834. Utmost misery is no big news.

The bourgeois problem is twofold:

(a) The core itself is in deep trouble. A social system can make do with starving masses, as long as its heart provides sufficient pump action: capitalist “heart” is a value pump, and for forty years the pump has not been delivering enough, however much profit is made by a minority of firms, and whatever money is created and going round.

(b)The heart of the matter is not the whole matter. US, European, Chinese, etc., capitalism cannot go on in an eruptive explosive world. Though eruption does not mean revolution (to give just one example, social violence in Bangladesh is as much related to religion as to class), but business needs a minimum of law and order as well as political stability.

We are not talking about countries or parts of the world (North/South, the West/Asia), but about “unequal development” within nearly every country. The ruling classes are not particularly worried about what goes on in a backwater Bolivian province, a miserable London estate, or a deprived Islamabad district, and just deal with it by appropriate doses of police beatings and public relief. A very different situation arises when Bolivian villagers, rebellious English youths or rioting urban Pakistanis create unmanageable political confusion, disturb the flow of national capital, disrupt world trade, and indirectly cause war and geopolitical chaos. Class struggle strictly speaking (viz. merely involving bourgeois v. proletarians) is not the only factor that sets capitalism off course.

Capitalism is based on conditions that must be reproduced as a whole : labour first, also everything that holds society together, not forgetting its natural bases. “Crisis of civilization” occurs when the social system only achieves this through violent tremors and shocks, which eventually drive it to a new threshold of contradiction management.

In our time, if capitalism finds a way out of the crisis, recovery will not be soft and irenic. Social earthquakes, political realignments, war, impoverishment will come together with consumer individualism in the shadow of a domineering State, in a mixture of modernity and archaism, permissiveness and religious fundamentalism, autonomy and surveillance, moral disorder and order, democracy and dictatorship. The nanny State and militarized police go hand in glove. In the emblematic capitalist country, New Orleans after Katrina in 2005 provided us with glimpses of a possible future : infrastructure breakdown, overburdened public services, effective but insufficient grassroots self-help, law and order restored by armoured vehicles.

Defining a crisis is not telling how it will be settled. No European or North American country is now approaching the point where class disunity, political confrontation, ruin of the State and loss of control on the part of the ruling class would prevent the fundamental social relation – capital/labour – from operating, but conditions are building up to create such a situation.

One thing is certain. The historical context calls for an even much deeper response than in the 1930s, and no solution is on the way, no “creative destruction”, to use a phrase coined by Schumpeter in the middle of a world war.

14 : Social Reproduction, So Far…

Unlike a bicycle that can be kept in its shed for a while, capitalism is never at rest : it only exists if it expands.

Social reproduction depends on the relation between the fundamental constituents of capitalist society. There’s no objective limit here. Labour may go on accepting its lot with 10% unemployed as with 1%, and the bourgeois can go on being bourgeois even if the “average” profit rate goes down to 1%, because global or average figures have meaning for the statistician, not for social groups. War brings fortunes to some, huge losses to others. There are times when the bourgeois will accept a 1% or 0% profit if he hopes thereby to continue being a bourgeois, and times when 10% is not enough, and he’ll risk his money and position to get an unsustainable 15%: then the break-even point becomes a breaking point. Capitalism is ruled by the law of profit, and its crises by “diminishing returns”, but this diminishing can hardly be quantified. This is why there have been very few figures in a study that wishes to assess the break in the social balance, viz. the contradictions able to shape and shake up a whole epoch.

(a) Which irreproducibility are we talking about ? Capitalism does not render its own production relationships null and void. No internal structural contradiction will be enough to do away with capitalism. To speak like Marx, its “immanent barriers” do not stop its course, they compel it to adjust: they rejuvenate it. The system’s social reproduction remains possible if bourgeois and proletarians let it go on.

(b) Only communist revolution can achieve capitalism’s non-reproducibility, if and when proletarians (those with jobs and those without) abolish themselves as workers.

(c) So far nothing shows that present multiple proletarian actions (defensive and offensive) point or lead to a questioning and overthrow of the capital/labour relationship.

(d) Therefore, capitalism nowadays has the means to reproduce itself. But as its long-term profitability deficit combines with growing geopolitical destabilization aggravated by globalization, its reproduction can only occur through disruption, violence and more poverty. Stalemate creates an ever more explosive situation, and present austerity now imposed on countries like Greece is a mild indicator of troubled times to come.

***

“The workers’ movement has not to expect a final catastrophe, but many catastrophes, political — like wars -, and economic, like the crises which repeatedly break out, sometimes regularly, sometimes irregularly, but which on the whole, with the growing size of capitalism,become more and more devastating. And should the present crisis abate, new crises and new struggles will arise”, Anton Pannekoek wrote in 1934, before reaching his conclusion: “The self-emancipation of the proletariat is the collapse of capitalism.” Today, unless revolution does away with a system that reactivates itself by periodic self-mutilation, we are in for more extreme and devastating solutions. (16)

NOTES :

(1) This is the 4th chapter of a book to be published by PM Press, From Crisis to Communisation. Other chapters deal with “Legacy” (the 60s-70s), the “Birth of a Notion”, “Work Undone”, “Trouble in Class”, “Creative Insurrection”, and “A Veritable Split” (a critique of some exponents of communisation).

(2) Marshall Sahlins suggested the existence of a domestic mode of production, based on a peasant household-centred economy, with little exchange and hardly any money.

From a very different angle, Materialist Feminist Christine Delphy takes up Marx’s concept and duplicates it. Domestic labour (performed within the family by unpaid women for the benefit of men) is theorized as specific enough to be the basis of a domestic orpatriarchal mode of production, which according to Ch. Delphy coexists with the capitalist mode in capitalist societies.

(3) On historical progress/regress: Detlev J.K. Peukert, The Weimar Republic: The Crisis of Classical Modernity, 1992 (German edition, 1987).

(4) Conan Fisher, The Rise of the Nazis, 2002. For a good book on Hitler’s Germany: Adam Tooze, Wages of Destruction. The Making & Breaking of the Nazi Economy, 2006. On the 1917-37 period, G. Dauvé, When Insurrections Die (1999), on the troploin site.

(5) E. Nolte’s The European Civil War 1917-45 (published in Germany in 1987) has not been translated into English. It is more ideology than history.

(6) E. Hopkins, The Rise & Decline of the English Working Class 1918-90: A Social History, 1991.

(7)J. O’Connor, The Fiscal Crisis of the State, 1973.

(8) There appear to be two trends among critics of capitalism in its neo-liberal phase. One school of thought, by far the best known, insists on the predatory role of finance over the “real” economy. Another school, without denying the impact of finance capital, doubts the present reality of this real economy. Though we won’t pretend to settle a difficult question in a few lines, that second tendency has the merit of questioning not so much the share of the profits appropriated by a tiny minority, but the materiality of these profits. According to writers like G. Balakrishnan (Speculations on the Stationary State, in New Left Review, # 59, 2009), technological and social development has been considerable – above all, in labour control – but has “failed to release a productivity revolution that would reduce costs and free up income for an all-round expansion” (Balakrishnan). See also W. Streeck, How Will Capitalism End ?, in New Left Review, # 87, 2014.

(9) Paul Mattick, Marx & Keynes. The Limits of the Mixed Economy, 1969.

(10) Tim Mason, Nazism, Fascism & the Working Class, 1995.

(11)Jean-Luc Gréau, L’Avenir du capitalisme, 2005. He used to be an economic expert for the main French business confederation.

(12) In Bhutan and abroad, critics have raised the point that Bhutanese society is far from the exotic heaven of peace and harmony that its elite claims to be ruling. Labour exploitation is fierce, traditions oppressive and minorities discriminated against. Well, only the gullible thought Shangri-La was real. But even if Bhutan was a tolerant, non-sexist, worker-friendly place, or if Gross National Happiness had been invented, say, in Denmark or Iceland, GNH would still be as misleading as GDP.

(13) For instance, as early as 1956, Günther Anders was writing on The Obsolescence of the Human Species.

(14) Clive Hamilton, Earth Masters. The Dawn of the Age of Climate Engineering, 2013.

(15) Sismondi (1773-1842) was one of the first under-consumptionist theorists. Observing the early 19th century economic crises in England, he thought competition led to excessive cost-cutting, which lowered wages and prevented the workers from buying what they produced. Sismondi’s remedy was to pay them more so they would have enough purchasing power.

(16) Anton Pannekoek, The Theory of the Collapse of Capitalism, 1934.

ie Einheit der deutschen Arbeiterklasse um 1900. Prokla 175, 6/2014

ie Einheit der deutschen Arbeiterklasse um 1900. Prokla 175, 6/2014